Ironton woman’s death made U.S. headlines 103 years ago

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, November 27, 2024

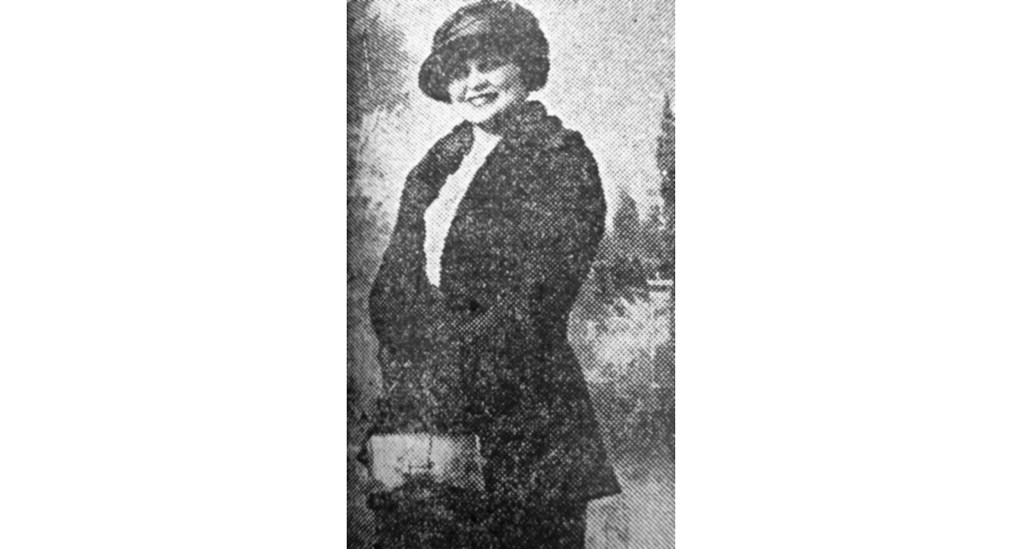

- Bonnie Storms Weiblinger, 26, an Ironton native, was performing as a chorus girl, under the name Bonnie Woodward, in New York City when she jumped to her death from a hotel window on March 5, 1921. (Ironton Register photo)

As journalists, our job is first and foremost to let readers know what is happening in their community, whether it is breaking news, previews of upcoming events or feature pieces on those around the region.

But another aspect is that, as a paper of record, we also serve as a keeper of history, giving future generations a resource to look back on life in Ironton and Lawrence County as it was.

New York City’s Somerset Motel, located on West 47th Street, was the site of Ironton native Bonnie Storms Weiblinger’s death. (Public domain)

This is quite evident in the bound volumes of not just The Tribune, but also its predecessor papers, The Ironton Register and The Irontonian, that we have here in our office.

The archives are a source of curiosity to our staff, as well as members of the public. We keep a 1912 edition, featuring the sinking of the Titanic open in the newsroom, and it has served as a conversation piece with quite a few visitors.

These dusty books date back to the late 1800s and in the yellowing and fragile newsprint contained in them are endless details of the past of our community, from the stories written by staff of yesteryear to ads for businesses long gone to public notices and announcements.

In perusing these volumes, one can see the development of journalism, changes in design and advances in printing that took place over decades.

One thing that stand out is, though photography had been around for decades, newspapers of the early 1900s contained little to no photos in the way of local coverage. The visuals that were featured came primarily from national sources, well into the 1950s.

Recently, when rearranging the office, I had to move a bound volume of The Register from March 1921 and decided to flip through it before putting it away.

The bulk of the main headlines that month were about the newly-elected president of the United States, Warren G. Harding, an Ohio native, and the appointments he was making to his administration, while considerable attention was given to Babe Ruth, who was aiming for another season home run record with the New York Yankees.

Being a fan of the silent era of film and 1920s culture, one photo caught my eye – from a front-page story detailing the death of a chorus girl in New York City, after she jumped from a hotel window.

The portrait of the young woman, 26 years old, looked quite similar to many a leading lady in the Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton films I watch often.

I assumed this was a national piece until I read closer and found the reason the story, which made the national wire and was featured in newspapers in multiple states, was given such prominent placement in Ironton.

Bonnie Storms Weiblinger was an Ironton native, the daughter of Henry Storms, a fruit farmer who lived on Hecla Street, and his wife, Mary.

One of 16 siblings, Bonnie had left home sometime after the death of her mother in 1914 and before her father passed in 1917.

Her brother, Henry, learned of her passing when word reached Ironton through headlines on The Register’s telegraph services that week.

On March 5 of that year, Weiblinger was staying in the Hotel Somerset, located at 150 W. 47th St. in the heart of Manhattan, two blocks from the site of where Rockefeller Center stands today.

The then-20-year-old hotel was popular with those in the entertainment business, hosting many an actress, singer and writer throughout its history.

Weiblinger, described as “most beautiful” by The Register, had been in New York for a few weeks to perform, under the stage name of “Bonnie Woodward,” with a traveling company in a show on at a 14th Street theater, while her husband, Lawrence Weiblinger, remained behind in Pennsylvania.

At 2 a.m. that night, she was found dead, having fallen from a high window in the building.

Her companion that night was John F. Berlin, the proprietor of Johnstown, Pennsylvania’s Crystal Hotel, who had known her for a year. The two registered at the hotel under assumed names.

Berlin said Weiblinger had arrived back at the Somerset late at night, after making a stop to see friends at a hotel across the street.

When she arrived at their room, Berlin said they “had words” and, at this point Weiblinger walked to the hotel’s window and opened it. Turning to him, Berlin said she told him, “Good-bye, Billie,” before jumping to her death.

When learning of her death, her brother was surprised to hear his sister had gotten into acting and had no idea she was performing. He said she had written him “a cheerful letter” a few weeks prior, telling him she was going to New York, and promising to write after she got there. It was the last he heard from her.

He told The Register in an interview that his sister had lived in Pennsylvania for several years.

By all accounts, the family home in Ironton was not a happy one.

Following her mother’s death and after Bonnie had left the home, her siblings had been removed from her father for neglect, then returned, then taken away again and adopted out.

News of Weiblinger’s death stayed front and center in The Register for the next several editions.

The paper reported that her family had been contacted by “a traveling man,” from Ashland, who said he had been in New York at the hotel the night of her death.

The man, who remained anonymous to the paper, told the family he had overheard “a loud quarrel” between Weiblinger and a companion, followed by a scream and her pleading not to be thrown out the window. The paper said the man was willing to testify and the family asked New York police to investigate her death as a murder.

It was there that The Register’s coverage of the matter dries up, with no follow up.

Online searches turned up no mention of a death at the hotel or anything on Weiblinger.

I called up my sister, Heather, who specializes in genealogy research and asked her to see what she could find.

Through ancestry and archive searches of other papers, she found that Weiblinger’s death made headlines in many states and an article from Georgia noted that police had questioned and released Berlin.

The report also stated that friends of Weiblinger told them she had been “despondent” for weeks and had threatened suicide.

Weiblinger’s body was returned to Ironton, and The Register reported she was to be buried in the family plot at Bald Knob Cemetery in Lawrence Township. Her father is listed on burial records as being interred there, though he has no marker. The same is likely true of her resting place.

Her husband never remarried and died in 1940. Berlin married later that year and lived until 1936.

The Hotel Somerset building still stand today, having undergone multiple renovations and redesign. Its first floor today is occupied by fast food restaurants, while its upper floors have been converted to apartments.

As for the anonymous Ashland man and his statement, no mention of him exists outside of The Register’s report.

Whether someone from this area had, through sheer coincidence, been staying at the same hotel that night and heard details that revealed more to this tragic story, is a mystery lost to the ages.

— Heath Harrison is managing editor of The Ironton Tribune. He can be reached at heath.harrison@irontontribune.com