Strange, but true: ‘Thar she blows!’ – Whaling was major industry in early American history

Published 12:00 am Monday, September 19, 2022

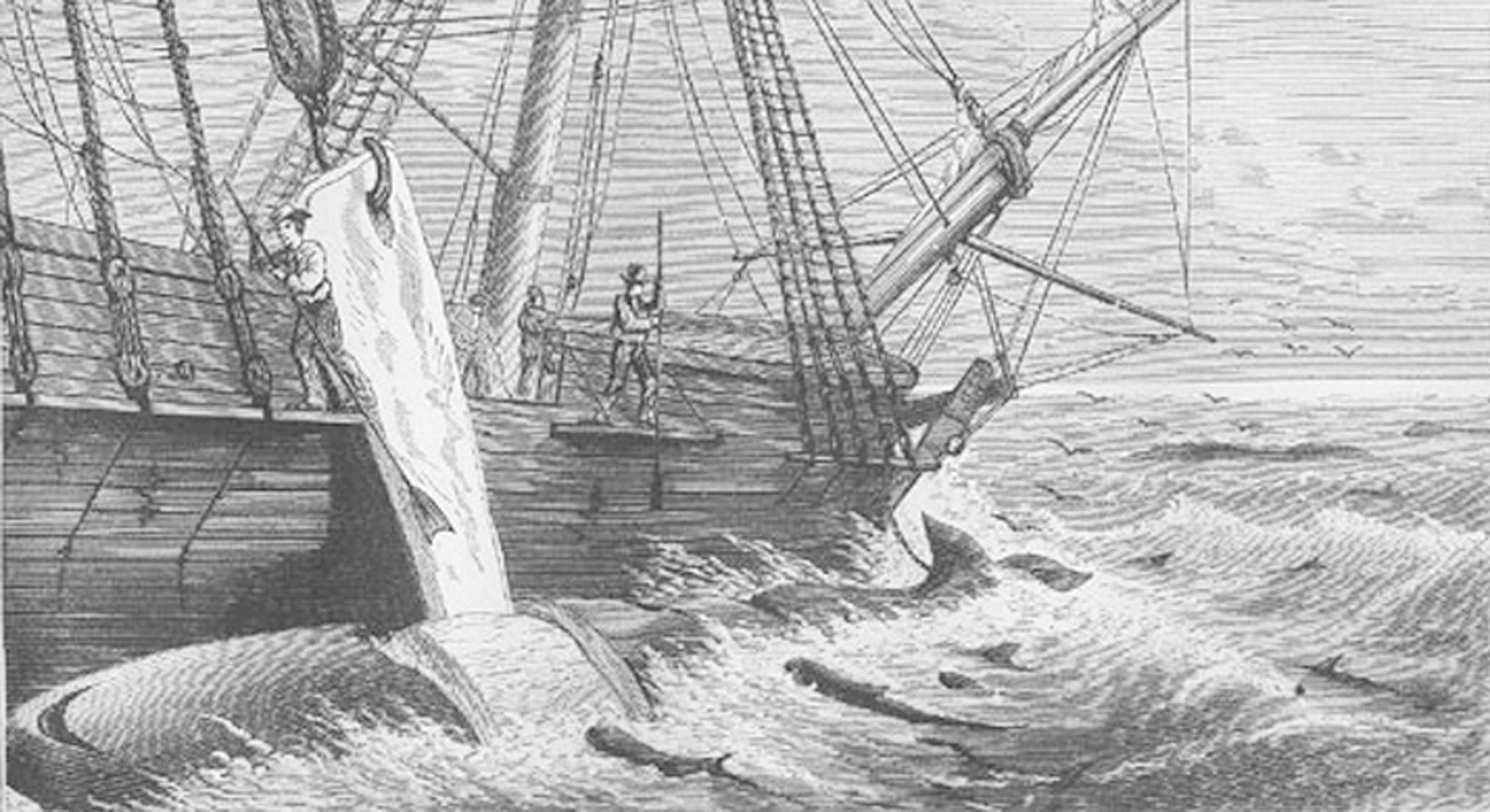

- Whalers flensing blubber from a sperm whale in this 1874 illustration.

By Bob Leith

For The Ironton Tribune

Whales are not fish! They are huge mammals.

A blue whale may grow to be 100 feet in length, others may measure only 15 feet in length.

There are two major groups of whales. A baleen whale does not possess teeth, but has hundreds of thin plates called baleen. The other type of whales is toothed whales. Baleen whales may live around 40 years.

Whales possessed three very valuable entities that men sought. Sperm oil was found in the whale’s head and its blubber. This oil was used in lamps for lighting and for lubricating machinery. Spermaceti was found in a whale’s head and was used to make fine candles. Ambergris was only found in sick whales.

The Charles W. Morgan, the last wooden whaleship in the world, docked at Mystic Seaport, Connecticut. (Public domain)

All whalers sought and hoped to find this substance, but few ever did. It would bring a market price of hundreds of dollars and was used to make perfume.

Long before any Europeans came to settle in America, there were whales in the sea and Americans to catch them.

These first American whalers were natives. They had no ships and could not go far out into the oceans. They waited for the whales to come to them. Dead whales would wash ashore and the natives would cut them up for their meat, bone and blubber. The natives would surround a large whale and quickly stabbed it with lances. If the hunters were lucky, the whale died from loss of blood.

Most of the time, the whale swam out to sea and the natives could not pursue it in their canoes. In Europe, the Basque people of southern France and northern Spain sought one particular species of whale – the “right” whale. These people felt this type of whale was the right, correct or perfect type to hunt because it was a slow swimmer, it floated when killed and had great numbers of baleen.

Americans on the northeast coast improved the native’s philosophy, techniques and equipment. They made stronger boats of cedar, harpoons and lances of iron and attached the rope of the harpoon to the whaling boat to exhaust the wounded whale. In the 1640s, Long Islanders made whaling a regular business. In East Hampton and Southampton, companies were organized to hunt for whales.

From the very beginning, lookouts were stationed along the beaches to watch for whales. If a lookout saw a whale, he yelled, “Whale off!” The men of the company would board the whale boats in six man crews. After a whale was caught, blubber was cut out. The blubber was “tried out” or boiled down to oil in big iron try-pots. The world needed whale oil for lamps and candles.

On Long Island, whale oil was used as money to pay debts and taxes. East Hampton paid its minister and school teacher partly in whale oil. For the children of Long Island, whale oil had a special meaning. Schools were closed during the whaling season (from December to April). Boys were expected to help try out the blubber.

In towns throughout the East, notices were posted:

“Landsment Wanted”

“One thousand stout young men, Americans wanted for the fleet of whaleships, now fitting out for the North and South Pacific Fisheries. Extra chances given to coopers, carpenters and blacksmiths.

None but industrious young men, with good recommendations, taken. Such will have superior changes for advancement….”

“Greenhorns” flocked to New Bedord, Massachusetts — farm, town and city boys eager for adventure. Agents met them and outfitted them, paid their boarding house bills and watched them closely. Not until the greenhorns were aboard a moving ship did the recruiting agents get their money. Sometimes, to make sure the greenhorns would report to the whaling ship on time, a prospective whaleman would be thrown in jail for debt and let out only when the whaling ship sailed.

No whaleman was ever paid wages. He would receive a share of the profits of the voyage called a “lay.” A captain’s lay might be 1/8, a cabin boy’s 1/250. An ordinary whaleman of the crew might receive from 1/160 to 1/100. All crew members were charged for clothes and other articles. When these charges were subtracted from the lay, a whaleman might end up a four-year voyage with less than $100 in his pocket.

A whaling voyage might last three or four years, or until the hold was filled with barrels of whale oil. The crew lived in cramped quarters, ate the same food over and over and awaited the yell of lookouts, “There she blows!” The whaling men talked, smoked their pipes, read, told stories of other whaling voyages, patched their clothes, sang songs and sometimes got on each other’s nerves and engaged in fist fighting, which was against the ship captain’s rules.

More than anything else, men on whaling ships scrimshawed. Scrimshawing was carving objects from the jaw and teeth of the whale. The men made all kinds of scrimshaw articles for their wives, sweethearts and friends. They carved rolling pins, clothespins, chessman, dominoes, rings, bracelets, canes, penholders, footscrapers, doorknobs and yarn winders. They carved thousands of jagging wheels which women used for crimping the edges of pie crust. All awaited the lookout’s notice of whales. It might take hours or weeks.

The lookout stood on two narrow pieces of lumber nailed to the mast. His only support was a pair of iron hoops at the height of his breast. The lookout was stationed 100 feet above the deck. The lookout sought to see the spout or water vapor caused by the whale’s breath. The lookout would relay the direction of the whale from their ship and the distance. Lookouts were on duty four hours, off duty four hours, and there were two watches of two hours each. When a whale was seen, whaling boats (three or four) were lowered and the chase was underway. The crew was there to kill whales and get oil.

The whaleboats had been serviced and supplied before the voyage began. Two wooden tubs in the whaleboat had coiled rope or 1,800 feet of line. Also in the whaleboats were harpoons and lances, cutting spades, oars and a rudder. There was a wooden bucket for bailing water, and bread and water should the whale boats be towed far from the ship. Ships were usually provisioned for two and a half years.

Each whaleboat was rowed by a crew of six men. Each whaleboat raced to get to the whale first. A harpooner stood in the bow of the boat and would possibly throw two harpoons into the whale. The headsman replaced the harpooner and went to kill the whale with a lance. If the whale “ran” across the surface of the water, the men in that whaleboat were off on a “Nantucket sleigh ride.” There were stories that told that the wounded whale took them so far on such a “sleigh ride” that they could never find their way back to their ship. If there were other whales in the vicinity, a “waif pole” was stuck in the whale. This pole told what ship had killed the whale and no one else was allowed to take it.

The 80-ton whale was taken to the ship by the oarsmen. The crew made a long platform. The head was separated from the body. The crew had to hurry as sharks came to feast on the dead whale. Men were trying to get pure oil from the head, spermaceti for candles and the jawbone and teeth for scrimshaw. The blubber was cut into long strips and hauled upon deck. The strips were cut into “blanket pieces” weighing a ton each, then dropped into the blubber room where they were cut into blocks called “horse pieces.”

The men hoped to find ambergris in the whale’s intestines. The crew yelled out “Five and 40 more!” A whale might have anywhere from six to 100 barrels of oil inside it. 45 was the number of barrels of oil taken from the average whale. Cutting-in was over and it was time for trying-out, or boiling the blubber into oil.

A wooden fire was started under the large try-pots on deck. Once the fires were hot enough, heat was produced by throwing scraps of blubber in the firebases. The men yelled out, “Bible leaves! Bible leaves!” These were the thinner pieces of blubber (like pages of a book) that were tossed into the try-pots.

After boiling the blubber, the oil cooled and was placed in barrels and put in the hold. Then a large cleanup occurred on the ship. When enough barrels were stored, the ship headed for home.

Americans sought sperm whales from 1712 on and they had their most successful whaling ventures from 1820 to 1850. The American whaling industry was represented by 70,000 persons. These American whalers killed 10,000 whales each year. The Americans’ whaling fleet numbered over 730 ships.

American whaling declined when the California gold rush occurred in 1840. As whaling continued into the 1840s, voyages began to last four to five years. The American Civil War (1861-1865) affected the whaling industry in such a way that it could not recover and whaling’s decline was quite evident throughout the second half of the 1800s and early years of the 1900s.

Whaling vessels left their ports from Provincetown on Cape Cod; from Sag Harbor on Long Island; from Edgartown on Martha’s Vineyard; from New London and Mystic and Stonington in Connecticut. However, the two most famous American whaling ports were Nantucket in southeast Massachusetts on Nantucket Sound in north central Nantucket Island and New Bedford in southeastern Massachusetts. Founded in 1760, it became the whaling capital of the world from the War of 1812 to 1860.

Often a Nantucket girl would refuse to marry a man until he had gone on a whaling voyage. On the roofs in Nantucket were “walks,” later known as “widow’s walks,” where Nantucket wives could walk and watch for incoming whaling vessels. A fire in the business district in 1846 and men leaving Nantucket to find gold helped bring on the death of whaling there.

New Bedford’s greatest whaling days came in the years 1825-1860. One New Bedford blacksmith, James Durfee, made 58,517 harpoons during his lifetime. Here, merchants gave their daughters a whale for a wedding present. In 1859, petroleum or “rock oil” was discovered in Pennsylvania. The world no longer needed whale oil for its lamps and celluloid replaced whale bone for use in women’s corsets. In 1925 the schooner John R. Manta, the last of the whaleboats to sail from New Bedford, completed its last voyage. The days of whaling were over.

Upon a visit to Yale University a few years ago, my family drove to Mystic, Connecticut and went to The Marine Historical Association’s Mystic Seaport. There, we saw the Charles W. Morgan, the last of America’s old whaling vessels. It was anchored offshore and the public could not go on board. It was built at New Bedford in 1841 and saw 80 years of service. She sailed more miles and captured more whales than any other whaler. She earned $2 million for her owners. Her last voyage ended in 1921. This day I was in Mystic, the crew gave a concert and storytelling of whaling history. “Gun ports” were painted on her hull to fool pirates who lay in wait to steal the whale oil.

Bob Leith is a retired history professor for Ohio University Southern and the University of Rio Grande.