Reds’ pitching great Maloney still going strong

Published 11:35 pm Wednesday, June 18, 2025

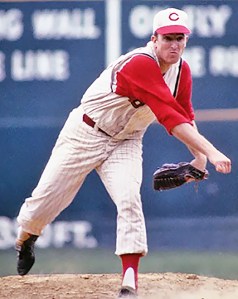

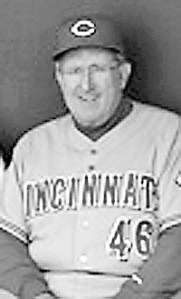

Former Cincinnati Reds’ pitching great Jim Maloney turned 85 years old on June 2. Maloney is the all-time Reds strikeout leader.

By Jim Walker

jim.walker@irontontribune.com

FRESNO, CA — Jim Maloney just turned 85-years old. He hasn’t pitched in the major leagues since 1970.

Trending

But the gifted right-hander has the same game plan for his life that he had as one of the game’s greatest pitchers.

“When I started a game, I was going to throw a perfect game. 27 up, 27 own,” said Maloney. “I would go one hitter at a time. If I got the first hitter out, I was going to get the next hitter out.

“If a guy got a hit, I was going to throw a one-hitter. I would try to throw a perfect game from there. That’s just for me. I stayed in that frame of mind. Every game I pitched I felt I had the ability to throw a perfect game every time I went out.”

“If a guy got a hit, I was going to throw a one-hitter. I would try to throw a perfect game from there. That’s just for me. I stayed in that frame of mind. Every game I pitched I felt I had the ability to throw a perfect game every time I went out.”

And that is the same game plan Maloney uses in his own life.

“I just take it one day at a time. My wife and I get out and do things. You have to keep moving,” said Maloney, who still participates in the Reds Fantasy Week and goes fishing for salmon in Alaska with his wife, Lyn.

It’s been quite an eventful 85 years for Maloney who is a member of the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame. He is an all-around athlete who is considered one of if not the best athlete to play at Fresno High School.

Trending

“I was interested in all three sports. I was interested in any kind of sporting thing outside. At the end of my junior year, my dad had talked to some (baseball) scouts. In those days they didn’t have the draft and (the scouts) had to go out to the games and look at the players.”

Fresno High School not only had Maloney, but future major league baseball catcher Pat Corrales who spent 50 years in the game as a player, manager and front office personnel, along with pitcher Dick Ellsworth who pitched eight seasons with the Chicago Cubs including a 22-10 year during his 12 seasons.

“We had a real good baseball team so we had scouts coming around and telling my dad that (Maloney) was going to get some money. In those days they had bonus contracts. Bonus babies are what they called them. It was 50 to 100 thousand (dollars). That was a ton of money in those days,” said Maloney.

“I talked it out with my dad and I stayed out of my senior year of football because I didn’t want to get hurt and miss out on baseball which was the sport I was really advanced in. I was about two steps better as far as my arm was concerned.”

Maloney’s father Earl Maloney owned a large used car dealership and talked with all 16 major league teams, serving in what is nowadays called an agent.

“They were offering 30 or 40 thousand dollars for me to sign and he said I was worth more money than that. I would have signed for a Hershey bar,” said Maloney.

Instead of signing, Maloney talked with Stanford but ended up at the University of California.

“I was like a fish out of water there, so I came back to Fresno,” Maloney said of his return home to play for Fresno City College for a semester.

Cincinnati Reds’ scout Bobby Maddix quietly came to Fresno to watch Maloney. Although he played mostly shortstop, he did pitch some. Yeah, he pitched. He threw 27 hitless innings.

Maddix told Maloney’s dad he had the money and the Reds came up with the $100,000 signing bonus.

With the money in today’s NFL, quarterbacks are making 40 to 50 million dollars a year. Maloney was clocked at 100 miles an hour crossing home plate, the exit speed that pitchers are clocked by in today’s game.

Despite the big football money, Maloney said he would still have gone with baseball.

“I would have gone baseball. I don’t believe I was equal to my ability to throw a baseball at that time. I could throw a football okay, but baseball was my deal all the way from day one,” said Maloney.

“I just liked to play all sports. At Cal, I went out for the frosh basketball team and I made the team. I played about a month and a half for the Cal freshman. I was a forward. I could dunk a basketball. I could jump. My specialty was rebounding. I could block guys out. I was a good athlete and it helped me in my pitching.”

Maloney spent one season in Topeka, Kansas, before being called up to the majors. He had a major league contract so he couldn’t be sent to a rookie league. He could only go to a B-league team. At Topeka, Maloney said he threw 160 innings after only throwing 27 innings for Fresno.

“They didn’t count the pitches. They just left you out there and let you go until they started hitting you and then the coach or manager took you out,” said Maloney.

Pitch count? We don’t need no stinking pitch count.

When Maloney threw his 10-inning no-hitter against the Cubs, he threw 187 pitches, struck out 12, walked 10 and hit a batter. He made his next start in which he worked 7.1 innings and got the win.

Maloney was 134-81 with a 3.16 earned run average in 11 years with the Reds. He threw three no-hitters plus a no-hitter that went 10 innings but he lost 1-0 in the 11th inning on a home run by Johnny Lewis.

”For a long time, they gave me credit for a nine-inning no-hitter, beat even though I lost the game.,” said Maloney who said. “In my mind, I got beat.”

Maloney was 13-3 with a 2.88 ERA in 1963 at midseason and selected for the National League All-Star team. He was informed of his selection before a game in Houston.

But after the game, Maloney was told he had to be removed from the All-Star team because the Chicago Cubs did not have a representative and he was replaced by pitcher Larry Jackson who was 9-7 with a 2.07 ERA.

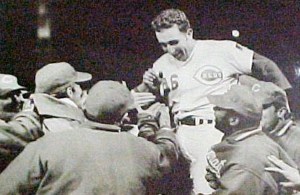

Teammates celebrates Jim Maloney’s 10-0 no-hitter over the Houston Astros on April 30, 1969.

In 1965, Maloney out-dueled Jackson and won 1-0 as he threw his first official no-hitter. Shortstop Leo Cardenas hit a home run off the foul pole leading off the 10th inning for the game’s only run.

His second official no-hitter came on April 30, 1969, when he beat the Houston Astros 10-0 at Crosley Field. Maloney struck out 13 and walked five. He said he used his own philosophy to stay focused despite the lopsided score.

“It was just like we said before, I went one hitter one pitch at a time. If a guy got a hit off me, that’s the way it was going to end up. A one-hit shutout,” Maloney said.

In today’s game, Maloney might not have gotten a chance to throw those no-hitters. Pitchers are on a pitch count — usually around 100 pitches — or just five total innings of work.

Maloney shakes his head at the pitching philosophies of today’s game.

“I don’t know what that is, but that’s the way they play it today. All the managers manage the same way. There’s no difference in them,” said Maloney.

Sandy Koufax (left) and Jim Maloney were the two hardest throwing pitchers in baseball during the 1960s. Maloney was clocked at 100 miles an hour when the ball was crossing home plate.

“We had managers like Walter Alston who did a lot of small ball when they had (pitchers Don) Drysdale and (Sandy) Koufax and Johnny Padres and those guys. Maury Wills would get on and steal second base and they’d bunt him over to third and manufacture a run or two that way,” said Maloney.

“Then you had the San Francisco Giants who had Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Orlando Cepeda. They had no speed so you didn’t worry about if they got on base. But they could hit it out of the ballpark. They played for big innings. They managed the game differently.

“Today’s managers all have the same book.”

Maloney won 10 or more games from 1964 to 1969 and amassed more than 200 strikeouts in four consecutive seasons. He was 23-7 in 1963 with 265 strikeouts and 20-9 in 1965 when he struck out 244 batters. His 1,592 strikeouts are an all-time Cincinnati team record.

He also went 16-8 in 1966 with 216 strikeouts and he was 16-10 in 1968 with 181 fanned.

Despite his production, Maloney said contract negotiations were always difficult, especially since baseball was still under the reserve clause and there was no free agency.

“I used to have problems with that contract. (General Manager) Bill DeWitt wouldn’t give his mother a three dollar raise,” said Maloney. “I had these 20-win seasons and they wanted to give me a three or four thousand (dollar) raise and I had to hold out.”

Maloney held out numerous times and in 1965 he was the last player to sign a contract in the majors. The Dodders tandem of Koufax and Drysdale held out as a team and went in there for their money. Juan Marichal was holding out and he signed, and then Koufax signed and Maloney was the last guy among the big name pitchers.

Maloney was making about $34,000 and wanted to hit $50,000 but the Reds were only going for $41,000. He was still at home and was helping his father planting tomatoes. He hadn’t picked up a baseball.

Phil Seghi came to Fresno and called Maloney’s father and said he had the contract at his hotel. The Maloneys went to the hotel and Seghi said they got it to $48,000. Despite protests from his father, Maloney signed the deal.

The papers were reporting Maloney turned down $65,000 which Maloney called “fake news. It was all lies.”

He made his first start of the season at home albeit several weeks into the season. It wasn’t a friendly reunion..

“When I went out to the mound, they booed like crazy. They thought I was greedy or something,” said Maloney. “Today, those millions are fired around and nobody says a thing about people making any kind of money. But if you win a couple of games the fans are on your side.”

Maloney missed being a vital part of the Big Red Machine when a ruptured tendon in his toe sidelined him early in the 1970 season and he was never effective again.

He was 0-3 in seven games in 1970 as he tried to pitch through the injury.

“It would have been nice but that’s the way it worked out,” said Maloney, not dwelling on what might have been but what is happening.

And it’s happening just one day at a time.