Strange, but true: 1977 — Justice, finally, for Henry Ossian Flipper

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, May 10, 2022

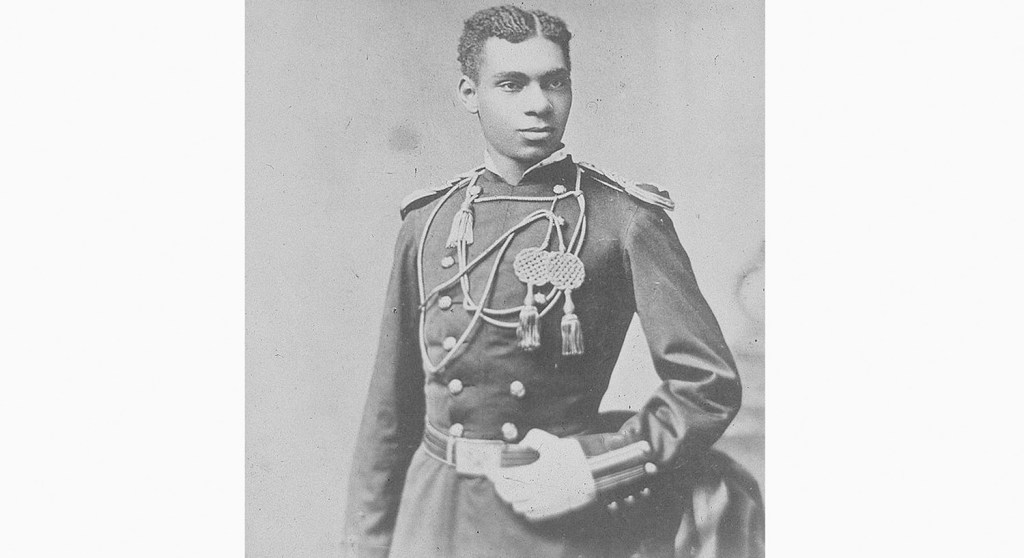

- Lt. Henry O. Flipper, circa 1877. (Photo: U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on Military Affairs)

By Bob Leith

For The Ironton Tribune

In 1619, the first African-Americans came to North America. When the Civil War began, the south held four million African-Americans in bondage.

Abolitionists pressured Abraham Lincoln to free these slaves. Lincoln studied plans to resettle these four million in the West Indies or Central America. Lincoln felt his primary focus was to preserve the Union and not agitate the “border states.”

Trending

On Jan. 1, 1863, the president issued the “Emancipation Proclamation.” This document referred to those slaves still in bondage in actual territories still held by the Confederacy. This was a wartime measure to weaken the Confederacy’s domestic labor force and many slaves ran away to Union lines.

To put “teeth” in this document, the 13th Amendment was passed and all slaves were now freed. Thus, in the latter stages of the war, the United States had two aims in the war. Lincoln had changed his mind and sought to destroy slavery. Many slaves stayed on the plantations and continued to work for their owners. Around 186,000 African-Americans joined the Union Army and 30,000 served in the Union Navy. Over and over, they proved themselves.

President Bill Clinton is surrounded by the family members of Lt. Henry O. Flipper, the first African American to graduate from the U.S Military Academy at West Point, as the Clinton signs a document pardoning Flipper for an 1882 Army conviction for conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman. (National Archives photo)

With their freedom declared, the former slaves stayed on the plantations, traveled to northern cities or sought to purchase their own lands. The Freedmen’s Bureau established schools, 4,000 in the south since many of the freedmen could not read nor write. Both Lincoln and his successor, Andrew Johnson, offered reconstruction plans with the goal of gradually issuing voting rights to the former slaves. These plans met opposition.

President Rutherford Hayes withdrew the occupation Union armies from the south in 1877. Southern whites, many who had been disenfranchised, started to fear the “Black vote.”

Starting in 1890 the right to vote from the African-Americans in 1896 by the United States Supreme Court. In Plessy v. Ferguson, the court established the principle of “separate but equal.” This decision is still viewed by many as a stain upon the integrity of the Supreme Court.

This decision applied throughout the United States, not just in the American south. The facilities were certainly separate, but hardly ever equal.

Trending

If the former slaves did not want to stay on the Antebellum plantations or grapple to survive in the large cities, they could look westward. Literally thousands moved west, hoping to avoid discrimination and physical abuse. There were Black cowboys like the great Bill Pickett. Some became law officers, ranchers or manual laborers who earned much needed pay to survive. Most of them became homesteaders on the Great Plains.

In the last years of the 19th century, Black regiments were found among the military posts of the west. The Native Americans they fought against called them “buffalo soldiers.” This label stuck because the they thought their black, curly hair was similar to the hair of the American bison.

The term “Jim Crow” was the name given to efforts to separate Blacks from Whites. The name was first used in the 1880s and flourished in the 1890s. It was not until the 1950s and 1960s that these discriminatory laws were done away with.

In 1970 Ray MacColl took a Black history course at Valdosta State College in Valdosta, Georgia. He would write his required term paper on African-Americans of the Old West. His professor gave him a grade of “C.”

He had run across the name of Lt. Henry Flipper in his research. MacColl made the experiences of Henry Flipper the passion of his teaching life. MacColl and Flipper’s niece decided they must remove the “black mark” on Flipper’s military record, especially since he was innocent.

Henry Flipper, depicted in The Colored American magazine, at age 44 when he was working as a civil engineer in El Paso. (Public domain)

Henry Ossian Flipper was born on March 21, 1856. He was born into slavery in Thomasville, Georgia. His father bought his mother and Henry from their owner.

In 1873, during the Reconstruction Era, Flipper was nominated to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. A white student offered Flipper $5,000 for his nomination. In 1877 Flipper became the first Black man to graduate from West Point. He became the only Black officer among 2,100 in the U.S. military.

He chose to serve with the “buffalo soldiers” who had poor horses, terrible rations and reused equipment. Despite the ever-present racial prejudice, the “buffalo soldiers” would win 19 Medals of Honor in multiple military campaigns.

Lt. Flipper reported to Fort Sill (now Oklahoma) and joined the 10th Cavalry in January 1878. He was friends with Capt. Nicholas Nolan, an Irishman. He escorted Nolan’s sister-in-law, Mollie Dwyer, on horseback rides. This enraged several white officers there.

Flipper was assigned to Fort Davis in Texas and was named “acting commissary of subsistence.” His new commander, William R. Shafter, did not like him and two other white officers decided to make his life unpleasant. In July 1881, Flipper discovered that someone had taken the commissary money from his personal trunk. Col. Shafter discovered the missing funds, arrested Flipper and was determined to instigate a court-martial.

On Dec. 8, 1881, Flipper was found innocent of embezzlement, but guilty of “conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman.” Flipper was dishonorably discharged at age 26. His post-military life was quite successful. He became a surveyor and mining engineer in the west, wrote several books, was a special agent for the Justice Department and became a special assistant to the Secretary of the Interior.

He never married and missed being a soldier. Nine times he tried to get his name cleared, but Congress refused him each time.

In 1931 he came to Atlanta to live with his brother. On April 26, 1940 Flipper, 84, died, still accused, but not guilty of any wrongdoing.

In 1975, MacColl and Flipper’s relatives presented their case to a lawyer. Due to MacColl’s persistence, the United States Army Board concluded the dishonorable discharge was totally inappropriate and issued Flipper an honorable discharge – 95 years after the court-martial.

The next year, 1977, MacColl and Flipper’s relatives witnessed the unveiling of a statue of Lt. Henry Flipper at West Point. In 1978, Flipper’s remains were reburied in Thomasville, Georgia, with full military honors.

Without the trumped-up charges, Flipper may have become America’s first Black general.

During the 113-day Spanish-American War in 1898, there were four Negro units in the American west. Among them were the famed 9th and 10th Cavalry. These units saw action at El Caney, Las Guasimas and San Juan Hill.

Even southerners, who were racially biased, stated that Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” would have been exterminated, if not for the bravery of the 9th and 10th Cavalry. In 1949 President Harry Truman moved to integrate the U.S. military.

Bob Leith is a retired history professor for Ohio University Southern and The University of Rio Grande.