Strange but true: There’s no Sundays west of the Mississippi

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, March 15, 2022

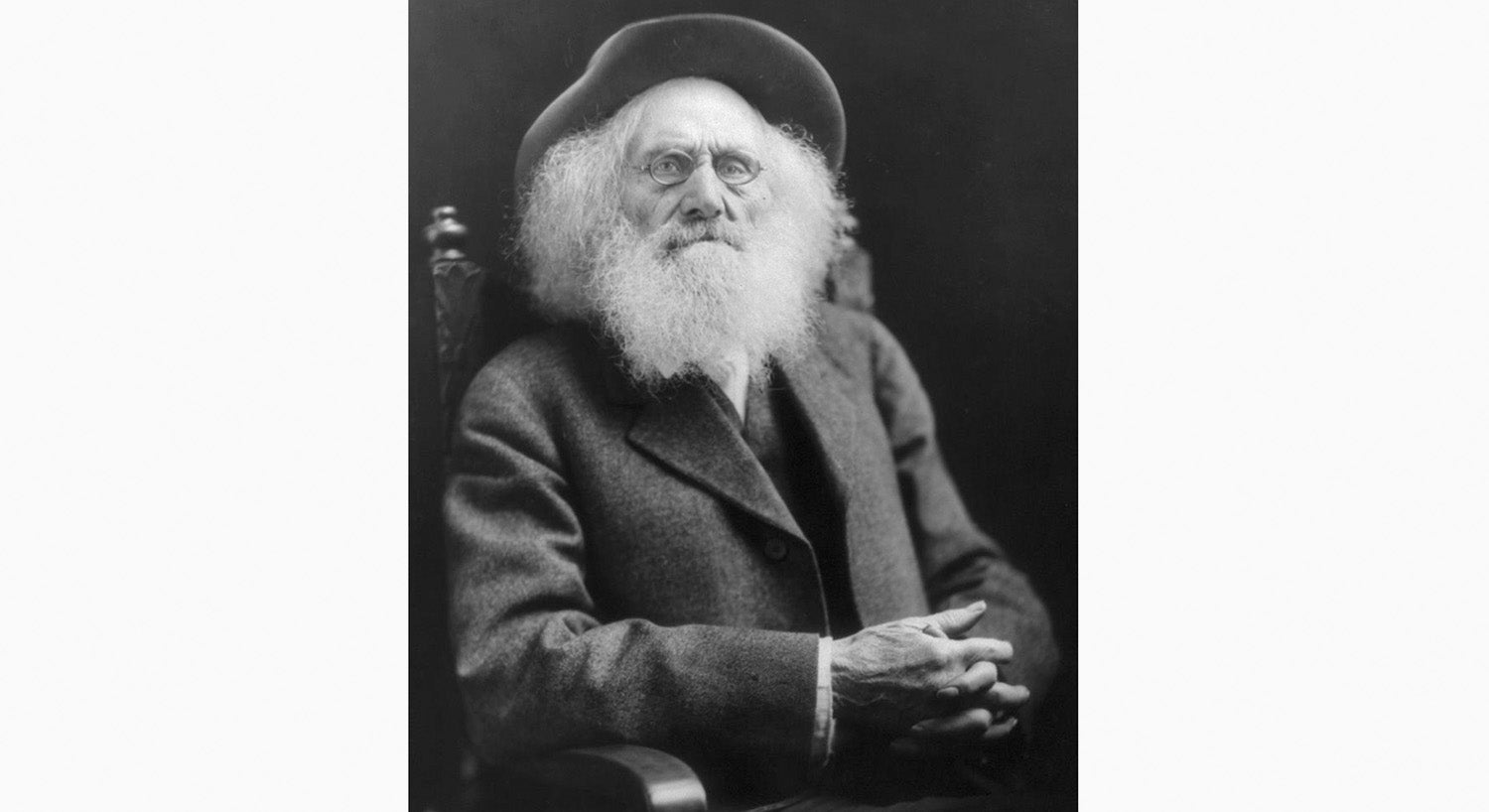

- Oregon Trail pioneer Ezra Meeker, as seen at the age of 92 on the cover of his book, “Ox-Team Days on the Oregon Trail. (Public domain)

By Bob Leith

For The Ironton Tribune

Lije Evans rode his mule home to his cabin. A few men had just tried to get Lije to go to Oregon with them. As he opened the cabin door, he saw his wife, Rebecca Evans, stooping at their fireplace.

Lije yelled out to his wife, “Get your breeches on, Becky. We’re going to Oregon.”

Trending

“Wauregan” was Algonquian for “beautiful water,” a reference to the Columbia River. This word is the origin of the name of that far-off country and today’s state.

Oregon Country was that region of western North America between the Pacific coast and the Rocky Mountains. It extended from the northern border of California to the southern border of Alaska.

At the beginning of the 1800s, it was claimed by Spain, Russia, Great Britain and the United States. United States’ claim to the area was based upon the voyage of Robert Gray, who reached the Columbia River in 1792 and the Lewis and Clark expedition, 1804-1806.

Oregon Trail: Independence Rock Wyoming, a large granite out cropping, was a major stop for westbound emigrants on the Oregon Trail in the 1840s and 50s. Named by the first party to stop here on Independence Day it became one of the iconic features on the trail.

For those who took the long trek to Oregon Country, most sought the fertile Williamette River Valley. If settlers took the 2,000-mile trail to Oregon, they had to consider selling their homes and lands and most of their possessions of any value. They would most likely say goodbye to their relatives and friends forever.

To get to Oregon, they had to cross thousands of miles of inhospitable and dangerous plains, deserts, mountains, rivers and forests on foot. In 1843, some very brave people (913) made the continental crossing. Most of them were women and children and no one expected them to reach Oregon – all 913 made it!

By 1870, approximately half a million had followed in their footsteps on what became known as the Oregon-California Trail. From 1843-1870, these travelers, known as “Overlanders,” had caught “Oregon Fever.”

Trending

These “Overlanders” followed a 2,000-mile-long trail that started at Independence, Missouri, the “jumping-off place” for those going west. The trail crossed Nebraska by following the Platte and North Platte Rivers. It crossed Wyoming, crossing the Rocky Mountains through South Pass.

The trail followed the Snake River across Idaho to the Columbia River. Wagon train travel was at its heaviest between 1842-1860.

Forts were built along the trail and provided supplies and repairs to the pioneers and their equipment. Near Fort Hall on the Snake River north of Pocatello, Idaho, these western pioneers had an important decision to make. They could continue in a north-westward direction and end up in Oregon.

Others, tempted by the lure of California’s gold fields, left the Oregon Trail and turned southwest heading for California. This cut-off from the Oregon Trail became known as the California Trail. Fort Hall offered the pioneers two options – Oregon and farming or California and mining.

Planning to go west took months of thought if the Overlanders hoped to survive and succeed. Families would gather in Independence, Missouri, to meet the guide who would lead them over the Oregon Trail and elect a captain who was the man in charge for five to six months.

The families would vote on trail rules and assign various duties to individuals. Perhaps the most important item for the 2,000-mile trek was the Conestoga wagon for carrying personal belongings and supplies. It was common knowledge that each family should need two horses, two mules and eight oxen to provide “animal power” for the long journey. Oxen were preferred because they were stronger and more sure-footed than horses.

These canvas-covered wagons were used to carry farming tools, seed, cooking pots, blankets and weapons the settlers were sure they would need. The floors of the wagons were curved so that items in the wagon could not shift far.

The covered wagon was boat-shaped, so that the wagon could be floated across calm streams. Over the top of the wagon, eight wooden hoops had strong white canvas stretched over them. The wagons’ axles were lubricated with bear grease.

Another type of covered wagon on the Oregon Trail was the “prairie schooner,” lighter and faster than the Conestoga wagon. Since it was so far to Oregon and the wagons were laden down with excessive weights, the settlers tried to lighten their loads by walking as much as possible – in all kinds of weather.

Oregon Trail pioneer Ezra Meeker meets with U.S. President Calvin Coolidge in 1924. (Public domain):

Men and boys, old enough to carry rifles, walked alongside the wagons that carried the women and girls. Younger children kept the cows and pigs in order.

A wagon train might possess 100 wagons at the outset. The settlers woke up at 4:30 a.m. to prepare for the long day. They were moving west by 6 a.m. each day. A wagon train stopped at noon for an hour of rest (primarily for the draft animals) and did not stop again until the end of the day.

Any who were not in line by 6 a.m. gave up their designated spot and had to fall in the dusty rear of the train. The captain’s loud authoritative voice shouting “Wagons, ho” and “keep moving” was a symbol the train had to make time. The wagon train traveled seven days a week. Thus, the saying “There’s no Sundays west of the Mississippi.” Wagon trains hoped to travel 15-20 miles per day.

The wagon trains assembled and hoped to begin their journey in May when the grass of the plains was green. The trail’s migrants hoped to celebrate Thanksgiving Day in the Williamette Valley of Oregon. Until wagon wheels had made ruts into the sod, it was easy to lose the way by getting off the trail.

The pioneers expected to spend five or six months on their journey. Their hope was to reach the Continental Divide in the summer months. The 430-mile stretch west of South Pass (the way through the Rocky Mountains) became known by the very visible “trail markers.”

Hardships and death awaited the travelers. Native American attacks, wild animals attacking their herds, swollen streams, being trapped by typhoid, malaria, smallpox, contaminated water holes, a scarce supply of wood, exhausted draft animals (shot or left to die) and the personal will to believe they could go on tested the most courageous travelers.

Accounts describe the fresh graves every 100-feet along the trail for hundreds of miles. By 1850 there were nearly 20,000 graves. Also along the trail were the carcasses of 9,700 animals. Besides the evidence of dead travelers and animals, the Oregon Trail was littered with 3,000 abandoned wagons, personal family furniture, extra food supplies and anything that would “lighten the load” for the exhausted oxen.

Native Americans would dig up graves to get clothing and shoes. Eventually, the Overlanders buried the dead after dark and built campfires over the graves. In the following morning, each wagon would ride over the graves to hide evidence with their wagon tracks.

Some of the smaller and weaker wagon trains completely disappeared due to starvation after losing the trail or at the hands of Native Americans – no one ever really knew what happened to them.

Each night, the wagon train sought to protect itself against dangers they could not see. They especially feared Native American attacks at night. After stopping each day, the wagons were driven into a hollow circle called a Night Ring.

With the exception of the guards on the perimeter, the people slept inside. Each wagon followed the one in front. So accurate the distances and so perfect the formation, it only took 10 minutes from the time the lead wagon stopped until the defensive ring was complete.

Cattle and pigs are kept inside the hollow ring and oxen and mules are allowed to graze through the night. Inside, supper is prepared, singing and dancing express a lighter mood and the travelers turn in around 8 or 9 p.m.

The blowing of the bugle will begin another 15 to 20-mile day. Buffalo chips (dried buffalo manure) gathered by women made nightly campfires possible as the plains were treeless.

Spain and Russia relinquished their claims to Oregon Country earlier than the British did. Oregon Territory was organized in 1848 and became an American state in 1859. Had we not been at war with Mexico, possible physical conflict might have occurred with Great Britain over Oregon.

Travelers on the Oregon Trail could never forget the challenges and tragedies they endured. Few turned back home. One man is known as the “Father of the Oregon Trail.” Ezra Meeker had gone west with his family in 1852. He lived there for 53 years. He returned to the Oregon Trail in 1906 and 1910 by wagon. In 1915, he went by car.

In 1924, at the age of 93, he went by plane. Meeker died just before his 98th birthday. He was preparing to take to the trail again in an automobile called the “Pathfinder.” The auto was built in the shape of a prairie schooner!

The men most famous for getting the Overlanders to the far west were Jim Bridger, Kit Carson and William L. Sublette, incomparable western scouts.

However, an Ironton resident and local historian traversed parts of the Oregon Trail. Steve Shaffer, he of upholstery expertise, is a student of western history. He saw the very wide, but not very deep, Platte River, walked in wagon wheel ruts and climbed Independence Rock, one of the most famous landmarks in the west.

This granite boulder is in south Natrona County in central Wyoming, on the north bank of the Sweetwater River. It is 1,950-feet long, 850-feet wide and 193-feet high at its north end. Trail travelers climbed the rock and carved their names and places from which they came.

Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and the University of Rio Grande.