Strange but True: “…I should never have been here.”

Published 12:00 am Sunday, February 27, 2022

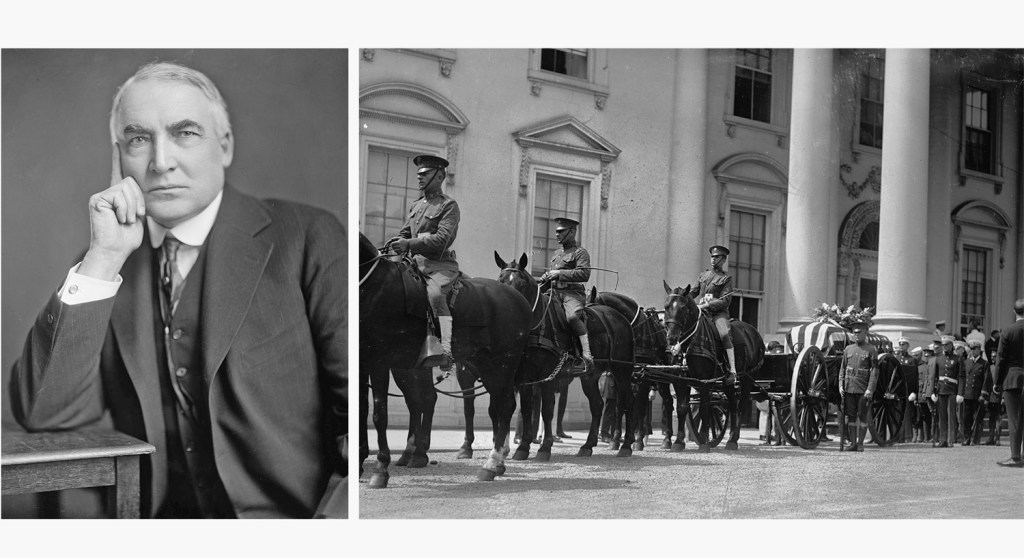

- Warren G. Harding, of Marion, Ohio, was the 29th president of the United States. His death in 1923 still leaves many unanswered questions. (Public domain) RIGHT: President Warren G. Harding’s funeral procession passes the White House in 1923. (Library of Congress photo)

Questions remain about the death of President Warren G. Harding, an Ohio native

By Bob Leith

For The Ironton Tribune

He looked as a president of the United States should look. He was very handsome! He may have been the friendliest man who ever entered the White House. He liked everyone and wanted to do favors for everybody.

Trending

As president, he wanted to help his neighbors in Marion, Ohio, his friends from campaign headquarters and the whole American public. He opened the gates to the White House grounds. He was loved by the public because of his bond with “Laddie Boy,” an Airedale dog who brought the president his paper each morning and retrieved his golf balls.

Florence Harding was the wife of President Warren G. Harding. She died in 1924, one year after his death. (Public domain)

The press asked the president if they might interview “Laddie Boy.” The president openly stated, “I cannot hope to be one of the great presidents, but perhaps I may be remembered as one of the best loved.”

At his death after two years and 151 days, he was mourned in the United States as only Lincoln had been mourned – until the stench of scandal in his administration became totally clear.

Warren Gamaliel Harding was born on Nov. 2, 1865, on a farm near Corsica, Ohio (now called Blooming Grove), five miles east of Galion. He was the oldest of George Harding’s eight children. Warren worked for his father’s newspaper, the Caledonia Argus. He would become a journalist in his adult years after reading law, selling insurance and teaching school in a one-room schoolhouse, “the hardest job I ever had.”

As a youth, Harding had loved all animals and avoided all fistfights. Everyone liked Warren.

He became a journalist when he and two friends bought The Marion Star. The Star had a circulation of 700. The three paid $300 for the paper and assumed its $900 in past debts.

Trending

Harding’s wife would change The Star’s “hanging by a thread” reputation. She tightened up the management procedures and spanked the newsboys when they made mistakes. One of those she spanked was the famous socialist Norman Thomas. The Star, under the wife’s influence, began to prosper.

President Warren. G. Harding aboard the presidential train in Alaska in July 1923, with cabinet secretaries. (Public domain)

In 1891, Warren Harding married Florence Kling De Wolfe, daughter of a prominent banker in Marion. Harding called her “Duchess” and it became well-known that she “called the shots” in the marriage.

She had a dominating personality as a divorcee. Her pressuring ways turned Warren’s newspaper into a success and she planned and persuaded him into events that thrust him into politics.

His marriage was less than happy and this caused him to battle depression. He felt more fear than love for her. Her dominant control of Harding sent him toward other women.

Harding told friends, “she makes life hell for me,” but he stayed with her. When extreme tension occurred in his marriage, he took multiple visits to a Michigan sanitarium – 5 times.

With Florence’s structured planning, Warren G. Harding served as an Ohio state senator and later, as a lieutenant governor of Ohio. His good looks and desire to please everyone carried him to a seat in the United States Senate, where he served six years without any major accomplishments.

Harding had been helped in state politics not only by his wife, but also by Harry M. Daugherty, a political strategist from Washington Court House, Ohio. In 1899, Daugherty said publicly, “Gee, what a great-looking president he’d make.”

The Republican Convention of 1920 took place during one of the worst heat waves in Illinois history. The temperature rose to 106 degrees at the Chicago Coliseum. The early nominees were part of a stalemate and the way was opened for a compromise candidate.

In George Harvey’s suite on the 13th floor of Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel, the famous “smoke-filled room,” 12 or 13 men met through the night of June 11 to try and break the Republican nominee deadlock. These political bosses asked Warren Harding if there was anything that might be held against him. Harding said “No!”

On June 12, 1920, senator Harding received 692 ½ votes on the 10th ballot to win the Republican nomination. His “No!” answer was not truthful, but “put him over.”

Probably no man with political aspirations would voluntarily admit his flaws of the past. Harding had bouts with depression that sent him to a sanitarium. He also had heart problems.

Warren had been involved in a 10-year affair with Carrie Phillips. The Hardings not only socialized with Mr. and Mrs. Phillips, but went on vacations with their neighbors.

A young girl named Nan Britton delivered news from her high school to The Marion Star. At the time of the “smoke-filled room” meeting, Nan Britton was the mother of Harding’s seven-month-old illegitimate daughter.

The president and Nan Britton met in disreputable hotels.

A book titled “The President’s Daughter” said that, according to Nan Britton, their child had been conceived in the Senate Office Building. At a little green house on “K” Street, Harding and the “Ohio Gang” played poker and consumed large quantities of liquor. Harding’s personal bootlegger, Mort Mortimer, would send his liquor-laden trucks to the front door of the house in broad daylight. Once, the president gambled away the White House china in a card game!

Warren Harding was a hardworking president. He found himself overburdened. He admitted to an aide that he was in over his head. He stated, “I am not fit for this office and should never have been here.”

Few accomplishments were recorded during the Harding presidency. Those few accomplishments were due to the efforts of his “Best Minds” (Mellon, Hughes, Hoover and Dawes).

By his third year in office, Harding was exhausted and in poor health. His blood pressure was too high, he was overweight and was often short of breath. A major problem at this time was the rumor of scandal involving those personal friends and the graft of those men in the “Ohio Gang.”

In the summer of 1923, the Hardings sought to escape Washington. A cross-country tour was planned. Harding called it his “Voyage of Understanding” and he would visit Alaska. He tried to relax, but rumors of Washington scandals wore on him heavily.

As the party traveled down the West Coast, Harding was afflicted by a violent stomach disorder. His doctor, Charles Sawyer, diagnosed it as ptomaine poisoning or indigestion from tainted crab meat. In San Francisco, Harding was put to bed. Harding’s menus and meals were scrutinized and it was found that crab meat was not served to him.

At San Francisco Harding’s mysterious illness turned into pneumonia. The president would die at 7:30 p.m., Aug. 2, 1923.

Other doctors contradicted the ptomaine poisoning theory of Dr. Sawyer and stated he had a stroke of apoplexy.

A rumor spread that Harding committed suicide by taking poison.

In 1931 Gaston Means, a Department of Justice detective, wrote a book titled “The Strange Death of President Harding” that suggested that Mrs. Harding poisoned Warren with the help of Dr. Sawyer.

Dr. Joel Boone, another doctor on the trip, was not allowed to care for Harding, but took notes based upon discussions with other doctors and his personal observations. Boone felt Harding’s death was directly related to his weak heart. Some reporters even suggested he died from a strawberry allergy.

Sawyer, throughout, gave Harding purgatives. After other doctors were called in, they issued the collective opinion that the cause of death was “cerebral hemorrhage.”

Mrs. Harding would not allow an autopsy and the exact cause of Warren Harding’s death is not known. Mrs. Harding would burn as much of his correspondence as she could find.

Harding’s body was placed on a special train. Along the route, thousands upon thousands of Americans gathered to see it pass by. Cowboys dismounted from their horses and took off their hats in the tribute.

A New York reporter said the demonstration was “to be the most remarkable event in American history of affection, respect, and reverence for the dead.”

The scandals of his administration would surface and diminish the nation’s high opinion of him and his presidency. In June 1931, President Herbert Hoover and ex-President Calvin Coolidge took part in the dedication of Hardin’s tomb in Marion – eight years after his death.

While taking several students on a statewide trip from Lake Erie to Cincinnati, we visited the Ohio presidents’ homes, burial places, schools and museums.

We, of course, toured the Hardings’ home in Marion. As I came down the stairs of their home, I noticed a Waterbury wall clock at the foot of the stairs. It was given to the Hardings as a wedding gift. It had worked well for years.

I know what had happened to that clock in 1973. I asked our guide about the clock’s strange reaction, but she said she did not know of it. I then told all about it.

This clock stopped at 7:30 p.m., Aug. 2, 1973 – the 50th anniversary of Warren Harding’s death. Efforts to repair it were futile. Then, after one week of inactivity, it began functioning again.

Why did this beautiful clock stop at the same hour, month and day fifty years after Harding’s death? “Clock Scientists” explained that something was left undone or unsaid by the president before he died on that date.

— Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and The University of Rio Grande