HISTORY LESSON: Sept. 1901 – An Ohio president dies in office

Published 12:17 am Saturday, October 3, 2020

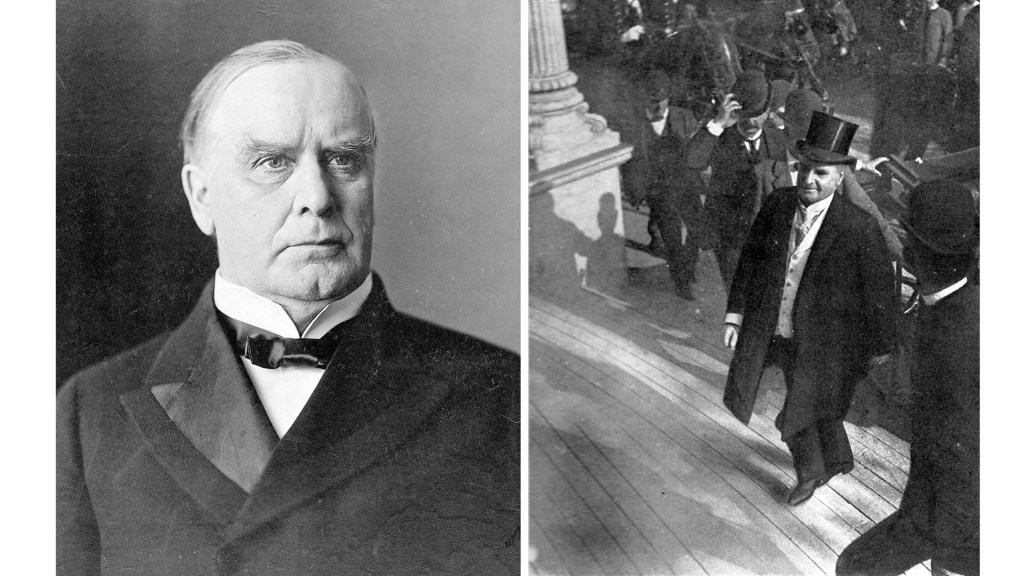

- LEFT: William McKinley, the 25th president of the United States, was a Republican and native of Niles, Ohio. RIGHT: In the last photo taken of him, President William McKinley enters the Temple of Music at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York on Sept. 6, 1901. Shortly after, he was shot during a reception in the building and died of his wounds eight days later. (Public domain)

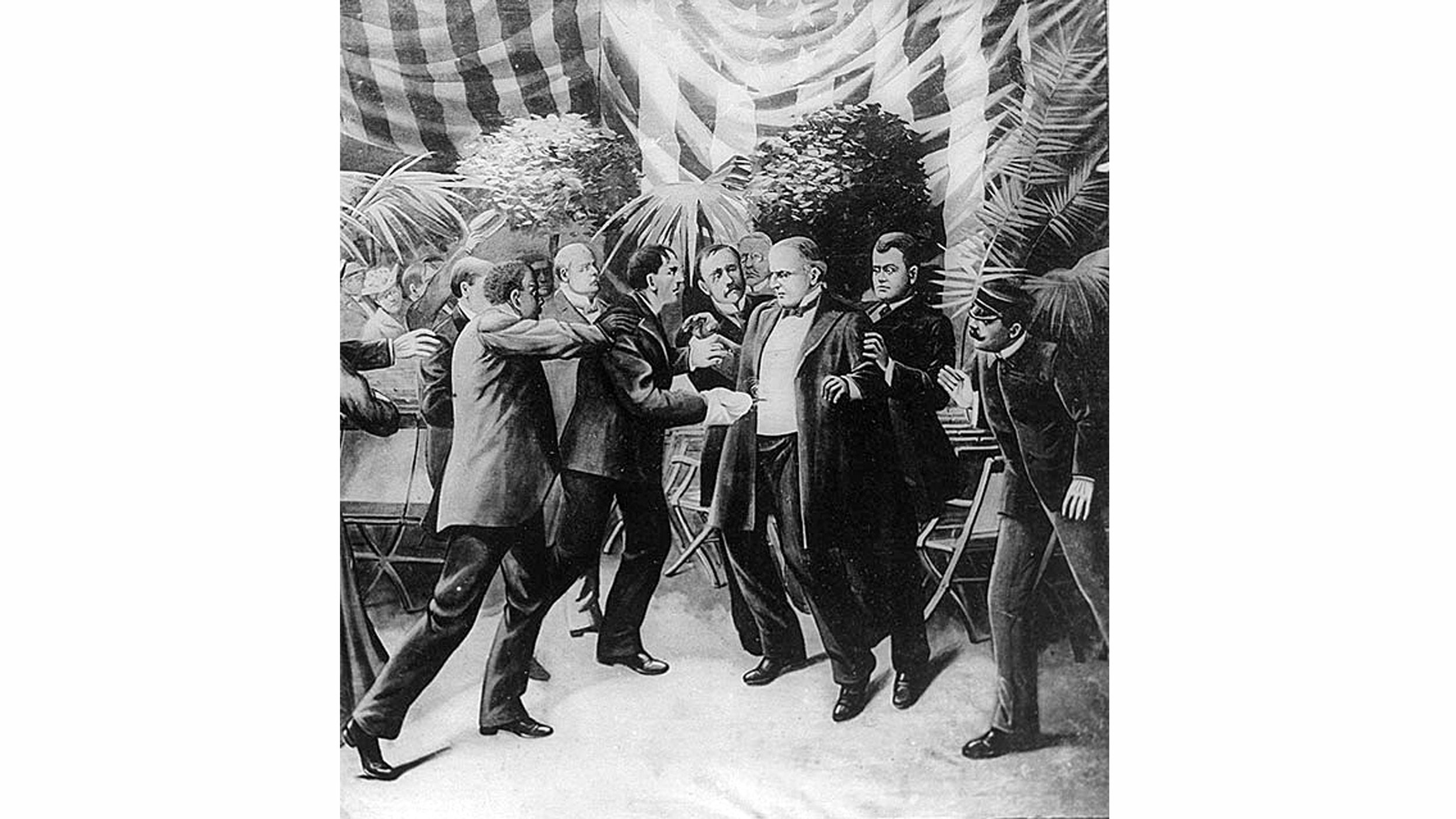

The assassination of William McKinley by anarchist Leon Czolgosz, on Sept. 6, 1901, is depicted in the artist’s conception by T. Dart Walker. McKinley died of his wounds eight days later. (Public domain)

By Bob Leith

The Ironton Tribune

Between 1861 and 1901, the White House seemed to belong to the Republican Party and former Civil War veterans.

The Republican sequence began with Abraham Lincoln. His vice-presidential running mate in 1864 was Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat, who ran on the Republican ticket due to his service as military governor of Tennessee, with the rank of brigadier general of volunteers. Following Johnson came Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Chester A. Arthur, Benjamin Harrison and William McKinley.

The lone Democrat to serve as President during this 40 year span was Grover Cleveland. He did not take an active part in the Civil War. In fact, he hired a substitute!

All of the aforementioned presidents (except Cleveland) were Civil War veterans and wore Union blue. In every presidential election, people of the era screamed, “Vote as you shot!” and Union veterans responded. McKinley was the last Civil War veteran to serve as president.

McKinley was born Jan. 29, 1843 in Niles, Ohio in an unpainted clapboard house on Main Street, the seventh of nine children. The bottom floor of the dwelling was a general store. His father was an iron manufacturer and oversaw blast furnaces.

His mother was a very devout Methodist. McKinley began his education in Niles, but when he was 9, his parents felt he was not receiving a good education. His family, except his father, moved to Poland, Ohio, and he entered a private school there. His mother hoped he might become a Methodist bishop. At age 17, McKinley enrolled in Allegheny College in Pennsylvania, but illness and a shortage of funds influenced him to withdraw. Upon returning home, he taught school near Poland when only 17 years of age.

When the Civil War began, McKinley was the first man in his hometown to volunteer. His mother was against his enlistment. He gained fame as a commissary sergeant at the Battle of Antietam, when he risked his life driving a mule-drawn wagon to take hot food and coffee to the Union lines. He called that Sept. 17 the greatest day of his life and was cited for bravery. He was discharged with the rank of captain and came home to study law. He began practicing law in Canton.

McKinley’s family did not possess wealth. He had had to withdraw from college, and he did not leave the Civil War with the highest military ranking. There would be many rungs to climb on the political ladder that took him to the White House. He was elected to Congress in 1876 and served all but two of the next 14 years. He fought for a high tariff to protect American industries and, in 1890, gave his name to the “McKinley Tariff Act.” It was one of the highest protective tariff bills in our history.

When McKinley sought an eighth term in Congress, he lost due to a gerrymandering action. Rebounding from this rare defeat, he sought the governorship of Ohio.

McKinley would be elected governor in 1891 and 1893. He gained widespread attention as governor of Ohio and met many individuals who possessed national influence, none more important in his life than Cleveland millionaire Marcus Hanna.

In 1893, McKinley cosigning a note, found himself in debt amounting to $100,000. Hanna and some friends paid off the debt and saved McKinley’s political career. Thus, Hanna began to promote McKinley and became business manager of the Republican Party. Hanna regarded William McKinley as the great admiration of his life and financed McKinley’s campaign for the governorship.

The Cleveland millionaire had higher aspirations for McKinley — the Republican presidential nomination in 1896. Hanna influenced the Republican convention to nominate McKinley.

McKinley admitted that he could not equal the oratory of the Democratic nominee, William Jennings Bryan.

Bryan traveled 18,009 miles and made over 600 speeches to 5 million people. He gave 36 speeches in one day! As Bryan stumped the country, McKinley refused to tour and conducted his campaign from the front porch of his home in Canton.

McKinley told Hanna he had “to think when I speak.” McKinley’s wife, Ida, was not well and he did not want to leave her and tour. Hanna raised more than $3,500,000 and said he would bring thousands of voters to McKinley’s home. He arranged cut rate excursions for people to come to Canton.

McKinley was coached on what to speak on and visitors had to agree to pre-arranged topics, questions and responses. During the summer of 1896, around 750,000 people came to McKinley’s home in Canton. McKinley was the first president to use the telephone for campaign purposes. With the support of big business and unbelievable advertising, he won in a landslide. Workers were told not to report to work on Wednesday morning after the election, unless McKinley won.

Ohio’s favorite son would only serve four years and 194 days as president, despite having been elected for two terms. He would be called “a white-livered cur” for opposing America’s great lust for war with Spain in 1898. He gave in to the warmongers and, in the peace settlement, Spain gave up its claims on Cuba and lost its hemispheric status. The United States received Puerto Rico and Guam. The U.S. later paid Spain $20 million for the Philippine Islands.

This war and its settlement established the United States as a world power. On Feb. 4, 1899, fighting broke out in the Philippines and the U.S. experienced its first overseas guerrilla war. McKinley was reelected in 1900 after prosperity was promised by the Republicans and a successful Spanish War was ended. The Republicans had endorsed the promise of “The Full Dinner Pail” for American workers. McKinley is considered the “first modern United States President” by some historians.

First lady Ida Saxton McKinley, the wife of President William McKinley, outlived her assassinated husband by six years. (Public domain)

McKinley was widely respected for his devotion to his wife, Ida Saxton. The McKinley’s daughter, Ida, died when she was four months old and Mrs. McKinley’s mother died in the same year. Their other daughter, Katherine, died at age four.

Due to her shock and grief, Mrs. McKinley became an invalid for the rest of her life. William McKinley became her constant caretaker. When her husband was governor of Ohio, Mrs. McKinley lived in a hotel room across the street in Columbus.

Each day, when McKinley went to the statehouse, he would turn and bow to his wife, watching from her hotel window. Every afternoon at 3 p.m., he would wave to her from a front statehouse window. As not to offend his wife in person, McKinley smoked from 50-100 cigars each week when with his friends.

At state receptions, President McKinley broke seating tradition. A president’s wife was supposed to be seated across the table from him. He placed his wife to his right so he could assist her if she had a seizure. If Ida had a seizure at a function, the President placed a napkin over her face. When the attack ended, he removed the napkin and table discussion went on as usual.

With a successful war concluded and prosperity evident throughout the nation, McKinley easily defeated Bryan again in the election of 1900. McKinley proudly announcecd, “I am no longer called the president of a party. I am now the president of the whole people.”

During the summer of 1901, McKinley left on a six-week tour across the American continent. He mingled freely with crowds, unafraid of danger. He said, ‘if it is in the mind and heart of anybody to kill me, he will do so for plenty of opportunity will be offered him.”

On Sept. 5, 1901, McKinley spoke to 50,000 people at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. The speech was one of his best and extremely important. The next day, Sept. 6, he was to appear in the Temple of Music at the Exposition for a public reception and a few minutes of shaking hands with the public.

George B. Cortelyou, the president’s secretary, had worried the public reception might be dangerous, so Cortelyou cancelled the reception. McKinley insisted the event be rescheduled. The event allowed the President 10 or 15 minutes to shake hands. McKinley said he would employ his “50-a-minute” hand shake routine — reach for a person’s right hand, grab it, turn the visitor to the right, let go of his hand and greet the next person.

In the line to shake McKinley’s hand was a 28-year-old man named Leon Czolgosz, son of a Polish immigrant. He worked in a Cleveland wire mill.

Leon Czolgosz, a second-generation Polish American anarchist, assassinated President William McKinley on Sept. 6, 1901. Czolgosz was convicted of the murder and executed by electrocution Oct. 29, 1901. (Public domain)

A self-declared anarchist, Czolgosz told a friend he wanted to kill a priest. The friend told him that there were so many priests and that a hundred priests would attend the funeral of the slain one.

Czolgosz felt it would be best to kill a “great ruler” — the president. At 4 p.m.. the handshaking began. McKinley always carried a good luck charm with him at all times — a red carnation that he wore in his lapel. He took the carnation and gave it to a little girl.

Minutes later, he was shot.

Czolgosz had bought a .32 caliber revolver and wrapped it in a handkerchief in his right hand. At 4:07 p.m., with only three minutes left to shake hands, Czolgosz fired two shots at McKinley.

People in the crowd began beating Czolgosz and McKinley said, “Don’t let them hurt him.”

McKinley was rushed to an emergency operating room on the fairgrounds. The doctors could not find the bullet and McKinley died a few days later at 2:15 a.m. on Saturday, Sept. 14.

On Oct. 29, 1901, Czolgosz was electrocuted. Authorities doused his body with sulfuric acid before the secret burial. In 1900, Theodore Roosevelt had been “kicked upstairs” — nominated as a vice presidential candidate with McKinley. “T.R.” was sworn in as President on Sept. 15. Mark Hanna declared, “That damned cowboy is President of the United States.” That cowboy became known as the “Trust Buster” and offered laborers a “Square Deal.”

Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and The University of Rio Grande.