Displaying the collections

Published 10:38 am Friday, April 3, 2020

- When the staff at the Huntington Museum of Art goes through their attics, they’re hunting for items for the next public shows, happy to share all they find for $5 or free. Just depends on what day of the week you drive up the McCoy Road hill. (Submitted)

Most people pop up to their attics looking for finds for their next garage sale.

When the staff at the Huntington Museum of Art goes through their attics, they’re hunting for items for the next public shows, happy to share all they find for $5 or free. Just depends on what day of the week you drive up the McCoy Road hill.

“We take a look at our collections and see what we have,” Chris Hatten, senior curator, said. “We try to present the collections in a new way. We want to show off our best treasures.”

Trending

This March started a run of two shows scheduled to go through early summer. “The Strong Melodious Songs: Artistic Images of Work” and “American Impressionism.”

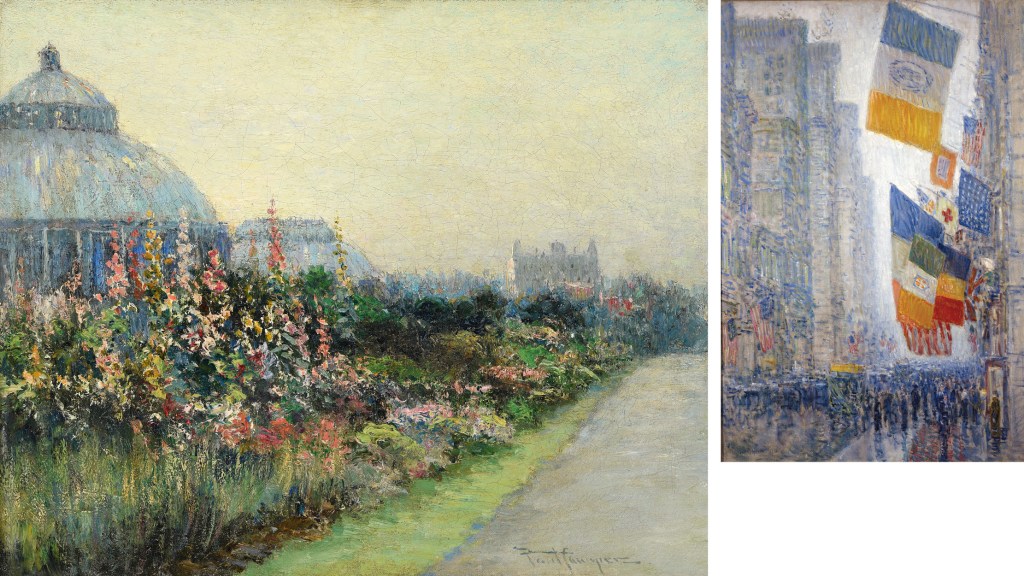

The Impressionism show features 30 paintings including Childe Hassam’s “The Flag,” a work Hatten calls the greatest painting in the museum’s collection. Hassam started his work in the late 19th Century, refining it as he worked into the next.

“We have the big names in American Impressionism,” Hatten said.

The reason they do is a bit of good luck, and the generosity of the Huntington community. When the museum opened in 1952, one of its benefactors was Chesapeake and Ohio Railway executive Herbert Fitzpatrick. A Virginia native, Fitzpatrick climbed the corporate ladder from lawyer to CEO at the C&O. Along the way he acquired paintings, prints, English silver and Islamic prayer rugs — and the 50 acres the 70,000 square foot museum now calls its home. Along with the main galleries at the HMOA, there are nature trails and a subtropical plant conservatory — all there for the visitors’ enjoyment.

“Fitzpatrick gave us some wonderful American paintings,” Hatten said. “‘The Flag’ is such a masterpiece. The beauty of the colors. You can see it was a rainy overcast day when it was painted.”

That rainy day was on Abraham Lincoln’s birthday in 1918, when Hassam had taken his paints and easel out to a city street in New York to capture a moment of an ongoing parade. Crowds must have abounded that day. But what Hassam saw was a flag blowing in the wind — a moment he turned into his classic work and gave another example of what it meant to be an American Impressionistic painter.

Trending

That style of art started in the 19th century in France as a rebellion against the more-staid Academic Style, whose artists wanted all rough edges obliterated from their canvases. Impressionists liked the rawness of what they saw out in the streets, out in the fields. And with perseverance and the toughness to reject the vicious criticism their works first attracted, they did. They turned their style of painting into an art form, now revered and still sought after today.

“It was a controversial style,” Hatten said. “The critics panned it. The Academics wanted something idealized, an elevated view. Impressionists wanted to paint what they saw at that moment, like a sunny day.”

But, as that century came to an end, the controversy dissipated. When that style crossed to the United States, it was embraced.

“Impressionism was a pre-eminent style in the U.S.,” Hatten said.

But in the 19th century as artists changed, museum visitors had to adjust how they approached a painting as well. The viewer had to have as much of an unorthodox style of viewing as the Impressionist had of painting.

“It was an energetic style,” the curator said. “People can see the art of painting. You will see the brushstrokes. In the Academic style, they would have smoothed that out.”

The reason for creating this newfangled way of painting? The answer lay in the technology that was sweeping Europe and moving over to the United States.

“You had a camera now,” Hatten said. “You wanted to do more than present mirror images of nature.”

So these maverick artists experimented by squeezing paints straight from the tubes, applying it raw to the canvas. They hauled their brushes and easels outdoors, setting up their studios on city sidewalks, looking, constantly looking for just the right moment to capture.

Giving them a boost in their search was the prosperity of the middle class that now had the time and the money to do what the rich people had been doing for centuries. Enjoy life. That gave the Impressionists different subject matter as artists sought to capture these nouveau riche through their oils and watercolors. Even painters known for one kind of work switched gears. And did it with great success. Like John Singer Sargent.

“We have a wonderful John Singer Sargent,” the curator said. “It’s a landscape even though he was known for his portraits.”

Another surprise in this show is getting to see a painting by Ohio-born Paul Sawyer, whose name more typically is synonymous with printmaking.

“We have an excellent painting of New York City,” Hatten said. “If they have just seen the prints, they need to come see this.”

The second show made up of paintings and photographs displayed in the museum’s Bridge Gallery gets its name from the Walt Whitman poem saluting the American worker.

Dominating the show is a painting, “Workers” by Ohio-born Robert Whitmore that the museum acquired in 2018.

“We started with that and looked for others to go along,” Hatten said. “It brings things together in a new way. It lets us do a unique show.

“Sometimes people are disappointed we don’t have these treasures out. This is a great chance to see the real prized works in the museum.”