HISTORY LESSON: July 2, 1881 From log cabin to poverty to assassination

Published 12:00 am Saturday, July 6, 2019

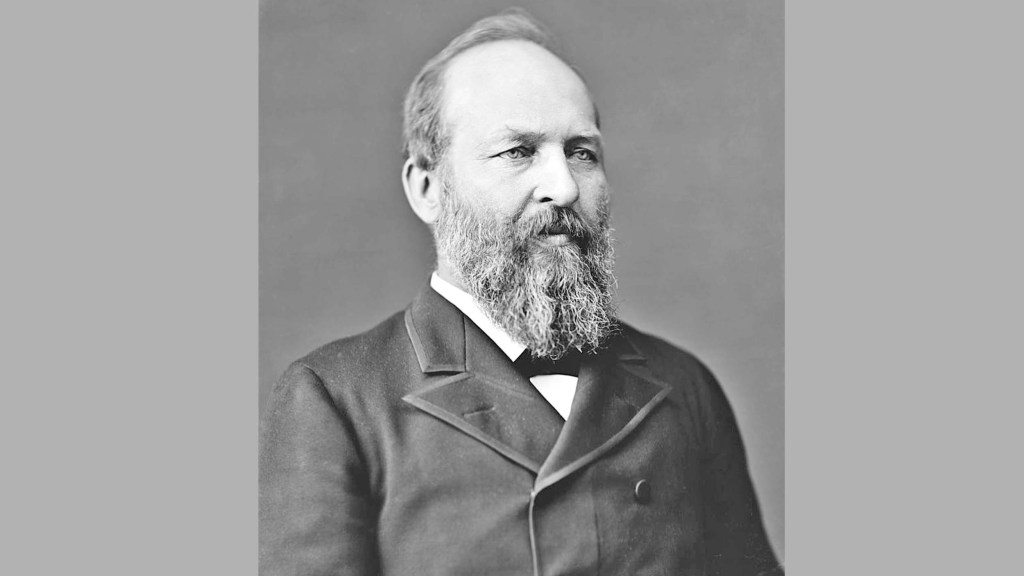

- Public domain James A. Garfield, an Orange, Ohio native, is seen in this photograph, taken in the decade before he became the 20th president of the United States in 1881.

Ohio’s James A. Garfield remains a forgotten president

Early life

He was born on Nov. 19, 1831 at Orange in Cuyahoga County, Ohio. He was left fatherless at age 2. His mother, Eliza, raised James and three other children in rural poverty.

He quickly learned to dislike farmwork. At age 16, he wanted to go to sea, but became a canal boy instead. His work as bowsman, deckhand, and driver on the Ohio and Erie Canal, but lasted only six weeks. He fell in the water 14 times and had an attack of ague (malaria?) that sent him home to recover.

James was determined to get an education. He had gone to district schools each winter for three months a year.

He was somewhat bored and attended a camp meeting and was baptized in the Chagrin River. This was the turning point of his life. He became ones of the Disciples of Christ.

He advanced his education at Western Reserve Eclectic Institute at Hiram, Ohio (now Hiram College). His unbelievable memory made him a prize scholar there. He next entered Williams College in Massachusetts and graduated in 1856.

After graduation, James Garfield found he had the gift of oratory. He returned to Western Reserve Eclectic Institute as a professor of ancient languages. He taught geology, Latin, Greek, higher math, philosophy, English literature and English rhetoric.

Besides this heavy academic load, Garfield became an ordained minister. At age 27, he became the college president. He entertained friends by simultaneously writing Latin with one hand and Greek with the other hand.

When the Civil War broke out, Garfield offered his services to Ohio’s governor. He became colonel of the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment, made up of many of his former students. He had to recruit soldiers, supply them and train them without any prior military experience.

He led a brigade at Middle Creek, Kentucky and took part in the battle of Shiloh. Garfield served bravely at Chickamauga. He became one of the youngest major-generals in the Union army.

Entering politics

Garfield resigned his commission in the army and was elected to Congress from Ohio. President Abraham Lincoln, with whom Garfield disagreed most of the time, told him major-generals were easy to find, but not good Republican congressmen.

Garfield was re-elected for 18 years and became the leading Republican in the House of Representatives. In 1880, Garfield was elected as a U.S. Senator from Ohio.

Rise to the presidency

Garfield went to the Republican convention to nominate Ohio’s John Sherman (brother of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman) for president in 1880.

The convention was noticeably split. One element, the “Stalwarts,” wanted President Ulysses Grant for a third term. The other element, the “Half-breeds,” wanted James G. Blaine, the “Continental Liar from the State of Maine.”

After 34 futile ballots, the Republican convention turned to Garfield. He became the nominee on the 36th ballot. He was stunned!

He was to run against another Union officer put up by the Democrats, Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, a hero of the battle of Gettysburg.

Garfield stayed behind the scenes at “Lawnfield” his farm in Mentor, Ohio. The “Canal Boy’s” star had risen militarily and politically.

The election of 1880 was one of the closet elections in American history. The Democrats attempted the number “329” to discredit Garfield. They placed this number on barns, fences, sidewalks and gutters.

Garfield was accused of being involved in the Credit Mobilier scandal. The Credit Mobilier was a dummy construction company set up to drain the assets of the Union Pacific Railroad.

Garfield was said to have been given 10 shares of its stock. Generous dividends left Garfield with a profit of $329. Thus, while a congressman, Garfield was accused of taking a bribe.

He defeated Hancock by 9,464 votes out of nine million cast. He became the third president born in Ohio, the third “dark horse” president and the last “log cabin” president. As our first left-handed president, Garfield was called “Canal Boy,” “Martyr President” and “Preacher President,” but detested the nickname “Old 329.”

An assassin strikes

Public domain

Charles Guiteau, a disgruntled office seeker, shot President James A. Garfield on July 2, 1881. The president died 80 days later and Guiteau was hanged on June 30, 1882.

On the morning of July 2, 1881, President Garfield was walking toward a train in a railroad depot in Washington, D.C. The train was scheduled to depart at 9:30 a.m. to take him to Williams College in Massachusetts, his alma mater. He was to give a speech there and enroll his two sons at the college.

He two sons and members of his cabinet were already on board. As he walked through the Baltimore and Potomac Depot with Secretary of State James G. Blaine, a shabbily-dressed man stepped behind him and fired two shots at point-blank range from a .44 caliber revolver. The first shot grazed his arm and the other lodged in his back.

The assassin had stalked Garfield for several days. He waited in Lafayette Park, facing the White House, night after night, but Garfield never came out. The shooter was Charles Guiteau, who had a long career of failure as a lawyer, evangelist and author. He said God had chosen him to “remove” the president to unite the Republican Party.

Public domain

This 1881 engraving, published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, depicts President James A. Garfield, center, after being shot by Charles Guiteau, at left, who is restrained by members of the crowd. Secretary of State James G. Blaine is shown supporting Garfield.

The president was mortally wounded and would go through 80 days of agony. The nation would make Garfield a folk hero.

The assassin rushed toward an exit and was stopped by Patrick Kearney, a District of Columbia patrolman. As Kearney took Guiteau to jail, the assassin told him, “I did it. I will go to jail for it. Vice President Arthur is president.”

Garfield was taken to a second floor bedroom of the White House. The doctors all agreed that Garfield’s back wound was too serious to allow removal of the bullet. Garfield’s chief physician, D.W. Bliss, told him his injury was formidable, but the president had a chance to recover.

Guiteau claimed he was an employee of “Jesus Christ and Company.” Prior to the shooting, he had started spending time at the Republican Party’s New York campaign headquarters in 1880. He moved to Washington, D.C. and visited the White House and State Department. He requested from Garfield and Blaine the position of consul in Paris, France. Blaine refused his request.

Battle for life

Garfield lingered between life and death for 80 days. Doctors continued to probe for the bullet. In late July 1881, the sweltering heat of Washington caused the president to have a fever. He normally weighed 200 pounds, but weighed only 120 pounds by late August. A primitive air conditioning system was implemented and huge amounts of ice were required. The temperature in the room was reduced from 99 degrees to the mid-70s.

The doctors agreed to move the president to an Oceanside cottage at Elberon, New Jersey. It was felt the salty air might help Garfield. A special train transported him and 2,000 local men built a railroad spur ¾ of a mile to the front door of Garfield’s cottage. Not to cause the president more discomfort, the men loosened Garfield’s railroad car and pulled by hand up an incline to the front door.

Garfield arrived there on Sept. 6, 1881. On Sept. 19, 1881, Garfield, after a valiant fight and much suffering, passed away at 10:35 p.m.

Alexander Graham Bell had been called to Elberon with his “induction balance machine.” The device was used to indicate the location of the bullet in Garfield’s back. Steel springs in the mattress created a field of interference and kept Bell from hearing the “click” that would locate the bullet.

The president died from an infection and internal hemorrhage. Today’s X-rays, surgery and antibiotics might have saved him. The doctor’s probes were not sterilized and some of their fingers went unwashed. Thus, the blood poisoning.

Aftermath

Guiteau was hanged on June 30, 1882 at the jail in Washington, D.C., despite presentation of an insanity defense.

He had felt the “Stalwart” wing of the Republican Party would rescue him since he had made Arthur president.

To his very end, Guiteau had claimed divine inspiration — “God’s act, not mine!”

James A. Garfield has been nearly forgotten in history by today’s world. His assassination has overshadowed his presidential accomplishments. He had said “Assassination could no more be guarded against than death by lightning.”

Bob Leith is a retired history professor for Ohio University Southern and the University of Rio Grande.