History lesson: Lawrence County named for defiant naval captain

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, March 29, 2022

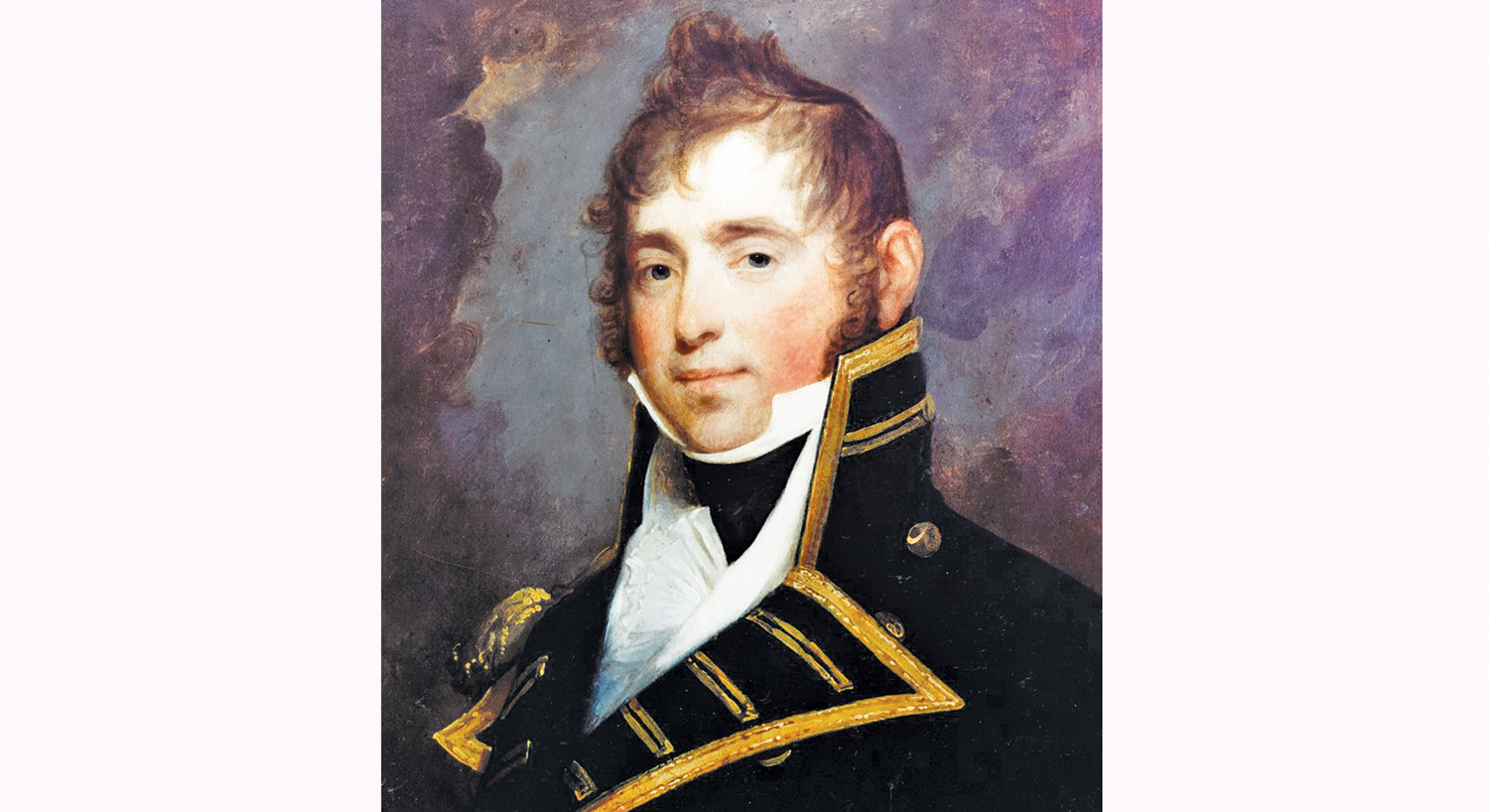

- Capt. James Lawrence, the namesake of Lawrence County, depicted in this oil painting by Gilbert Stuart from 1812. (Public domain)

By Bob Leith

For The Ironton Tribune

There should never have been a War of 1812 or “Mr. Madison’s War,” as the Federalists called it.

If President Thomas Jefferson considered public opinion and national insults to the United States, war probably would have come in 1807. Anti-British feelings escalated in the summer of 1807 due to the “Chesapeake Affair.”

On June 22, 1807, the United States frigate Chesapeake was 10 minutes out of Norfolk, Virginia, when the H.M.S. Leopard addressed her and asked to inspect its crew. The American commander, Capt. James Barron, refused the British request and the H.M.S. Leopard fired three broadsides into the Chesapeake, killing three men and wounding 18. The British carried away four seamen — a black man, an Native American, a native of Maryland, and a British deserter from their Navy.

National outrage nearly forced us into a second war with the British. The Chesapeake had gone out of Norfolk without one gun in condition to fire.

Jefferson did not want war and thus, employed his philosophy of “peaceful coercion.” In December 1807, Congress passed Jefferson’s “Embargo Act,” forbidding any U.S. ship to sail to any foreign port. This “Embargo Act” failed, as the American economy was badly damaged and some New England Federalists talked of secession at Hartford, Connecticut.

War did come, however, on June 18, 1812. The United States accused Britain of obstructing maritime trading rights as a neutral and impressing American seamen into the British Navy illegally.

Also, a faction in Congress wanted to annex Canada and Florida. It was also believed Indian raids were supported by the British. The total strength of the American Army was only 10,000 troops. These troops consisted of uncooperative militia and white-haired generals.

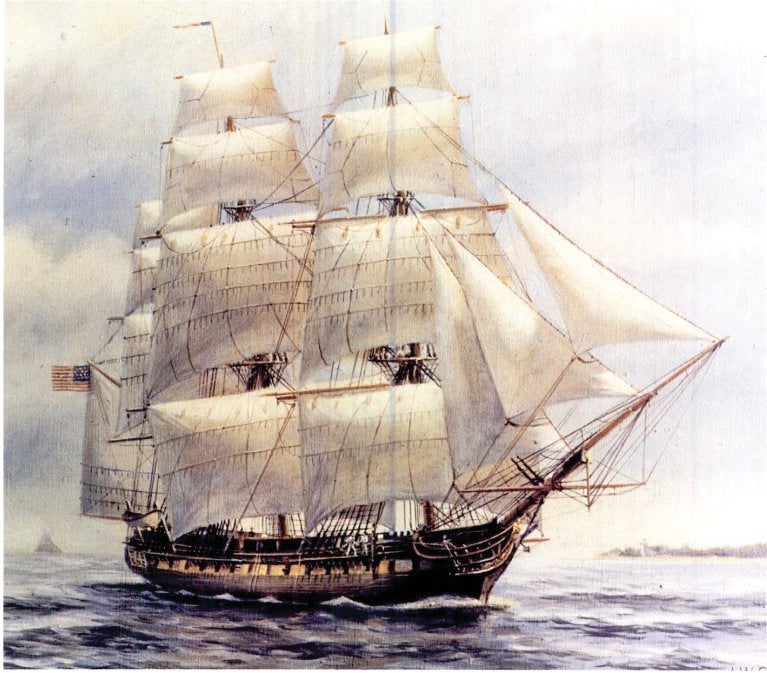

Land battles during this war would pale in significance in comparison to U.S. Naval successes. Great Britain had 600 ships in her Navy, of which 120 were “ships of line.” The United States had only 16 seagoing ships and 200 gunboats.

Naval efforts in the War of 1812 would produce notable victories and a few naval heroes. One such naval officer was James Lawrence, born in 1781 and educated in Burlington, New Jersey.

Lawrence’s father wanted him to become a lawyer, but James preferred the Navy to law. He enrolled as midshipman in the U.S. Navy in 1798. In 1802, Lawrence became a first lieutenant and would aid Stephen Decatur in burning the U.S.S. Philadelphia. Lawrence here won a reputation for gallantry. During the War of 1812, Lawrence commanded the U.S.S. Hornet.

The 18-gun Hornet defeated the 16-gun I-I.M.S. Peacock in February 1813 while losing only 3 men. On May 1, 1813, while in command of the Navy Yard at New York, Lawrence was expecting to be transferred to the U.S.S. Constitution. Instead, he was ordered to take command of the U.S.S. Chesapeake at Boston. This was the same frigate famous for its humiliation by the H.M.S. Leopard in 1807.

Lawrence was eager to prove his victory of February 1813 was no fluke. Lawrence’s crew was not properly trained when Capt. Philip Broke, a British officer, sent Lawrence a challenge to confront the H.M.S. Shannon (52 guns) – to meet him “ship to ship, and to try the fortunes of our respective flags.” Lawrence left Boston on the US.S. Chesapeake on June 1, 1813.

Broke awaited Lawrence between Cape Ann and Cape Cod. On June 1, 1813, both ships began battering each other with broadsides. Within 15 minutes, the Shannon’s better-trained crew proved its dominance. The decks of both ships ran red with blood, despite the layers of sand.

Lawrence would be wounded by two musket balls and would be taken below deck, despite demanding to be carried to the main deck. Practically all the Chesapeake’s officers were killed or wounded. Broke’s boarding party engaged the Chesapeake’s survivors in hand-to-hand combat. The Chesapeake would be taken and Lawrence died on the way to Halifax.

James Lawrence whispered words to his men in defiance of the British boarding party.

He uttered: “Don’t give up the ship! Fight her till she sinks!” These words now represent the motto of the United States Navy.

The Shannon’s victory restored British naval pride and was the “beginning of the end” for America’s deep-water fleet.

On Sept. 10, 1813, Commodore Oliver H. Perry fought the British in a Naval confrontation called the Battle of Lake Erie. Perry’s flagship was the U.S.S. Lawrence and he unfurled his flag, a nine-foot square of blue on which white letters a foot high proclaimed the words of the dying James Lawrence: “Don’t Give Up The Ship!” The Lawrence was badly battered but not given up during the battle.

On March 22, 1820, an American Naval hero was killed in a duel at Bladensburg, Maryland. He was killed by Commodore James Barron, commander of the ill-fated Chesapeake in 1807. The deceased served on a court-martial which tried Barron for his conduct on the Chesapeake. The Naval hero who died as a result of the duel was Stephen Decatur, whose last words were: “I have never been your enemy, Sir!”

Although the War of 1812 is probably the least-known American war among the general populace and is not taught in any great depth in our schools, it did produce two essential moments in American mythology: Dolley Madison’s saving Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington and Francis Scott Key composing the poem that became our National Anthem.

The years 1807-1820 have contributed to the place-name nomenclature of Ohio’s southernmost county: Burlington, Chesapeake, Lawrence and Decatur. In tribute to the courageous James Lawrence, our county was organized on March 1, 1816 and legally instituted in December 1816.

Bob Leith is a retired history professor for Ohio University Southern and the University of Rio Grande.