Strange but true: ‘Niagara’s Greatest Drawing Card’

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, March 8, 2022

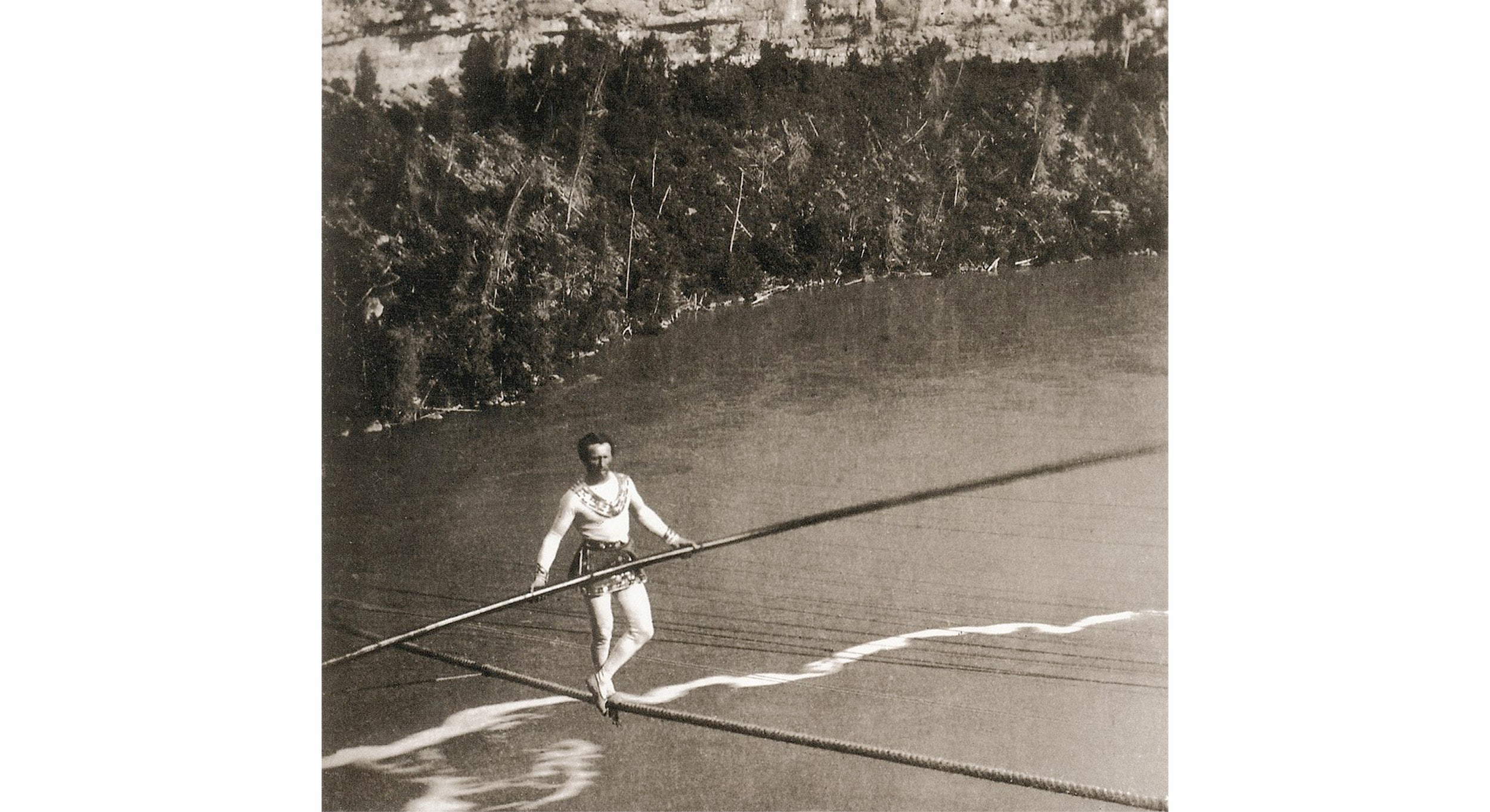

- Jean François Gravelet, aka “The Great Blondin,” crossing the Niagara River in 1859. (Public domain)

By Bob Leith

For The Ironton Tribune

A series of waterfalls on the Canadian and United States border at Niagara Falls, New York, is one of nature’s most spectacular sites. These falls were formed about 12,000 years ago. These falls pour more than 100 million gallons of water a minute into the Niagara River. The two major falls are the Horseshoe Falls, on the Canadian side, and the American Falls, on the United States side. Six percent of the water passes over the American Fall and 94 percent of the water passes over the Horseshoe Fall. The boundary line between the United States and Canada passes through the center of Horseshoe Fall. The Niagara River, 36-miles long, receives the falls’ water and connects Lake Erie with Lake Ontario.

These falls were well known to many tribes of Indigenous Americans before Europeans came to the United States or Canada. The French explorer Samuel Champlain became the first white man to see the falls. Louis, or Father, Hennepin (1640-1701) traveled with La Salle and left the first written account describing Niagara Falls. In a book published in 1683, Father Hennepin wrote, “These waters foam and boil in a fearful manner. They thunder continually.” The name Niagara originates from the Iroquois word Onguiaahra, which means “the strait.”

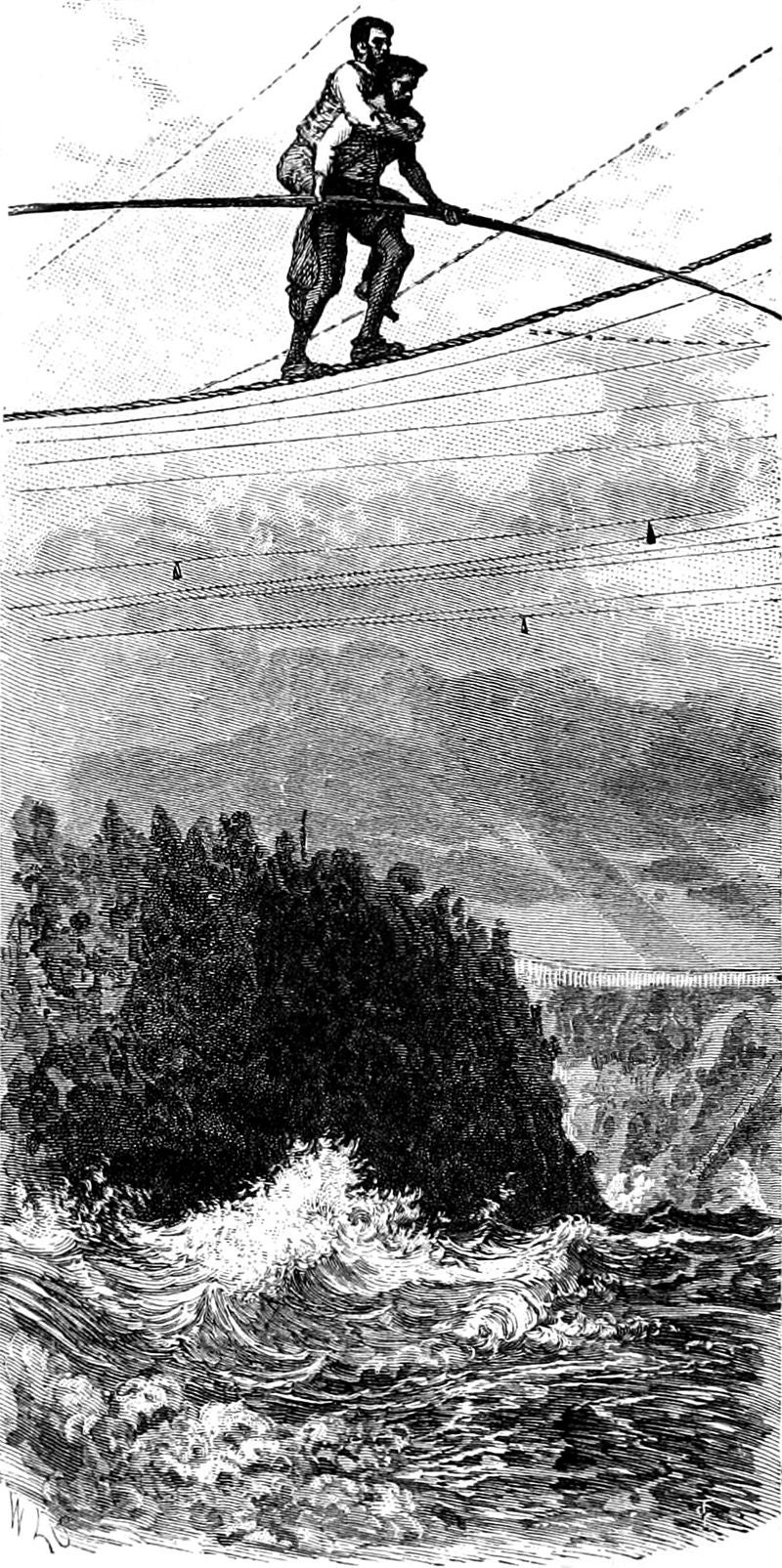

Engraving (c. 1883) depicting The Great Blondin crossing Niagara with his manager, Harry Colcord, on his back. (Public domain)

He was a small Frenchman with blue eyes and wavy blonde hair. He was only 5’5” and weighed 140 pounds. Jean Francois Gravelot was far better known as “The Great Blondin.”

Few people today have heard of him and many would have difficulty pronouncing his name correctly or trying to spell it. The Great Blondin had developed incomparable coordination on the tightwire during years of experience working for theaters and circuses. He began experimenting on the tightrope at age five.

On Thursday, June 30, 1859, the little Frenchman who had come to the United States in 1851 announced that he was going to walk across the terrifying gorge of the Niagara River about a mile below the falls. He would walk on a slender rope cable, 190 feet above the swift moving river. He would be dressed in tights and would carry a long balancing pole. At least 10,000 spectators awaited his walk. Men who were watching had bet large sums of money concerning Blondin’s success or fall into the river.

People of fashion, wealth, beauty and leisure always spent time at the falls during the summer season. The areas on both sides of the Niagara River were lined with people seeking to make a few dollars. In fact, Blondin had come here to earn a few dollars before signing on with an equestrian troop later on. Restaurants and drinkeries eagerly awaited the crowds, as well as people charging fees to see two-headed calves and bearded ladies.

The rope cable he would walk across was two inches in diameter and 1,300 feet long. In reality, there was only about 1,200 feet of cable over the gorge. Some 50 feet were consumed by the sag in the cable’s center and there were a few feet at each end to provide safe anchorage. Allowing for the sag and the installation of guy ropes, Blondin was actually 190 feet above the Niagara River.

He began his feat on the American side and it took him 17 and a half minutes to complete the walk. When he arrived on the Canadian side, Blondin told reporters he would cross back over to the American side in half an hour. Blondin planned a Fourth of July crossing. Every vantage point — trees, rocks and chairs — was taken by a huge crowd. Most of the crowd felt Blondin would certainly fall this time!

Blondin began his walk without his 38-foot balancing pole. Halfway across, he lay down full length on the cable, got up and walked backward swiftly, and stopped to take a flask from his pocket and drank. He then finished the walk. After resting an hour, Blondin appeared on the Canadian side waving a sack. The sack was put over his head and the sack fell to his knees.

He thus could not rely on eyesight, arms or hands. On July 15, newspapers reported what was to be Blondin’s farewell performance. On that date, he walked backward from the American to the Canadian side. Coming back to the American side, Blondin pushed a wheelbarrow. As the crowds continued to grow, a farewell at this time was not feasible.

As crowds kept increasing, Blondin stayed at Niagara Falls, New York, and announced on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 1859, a fourth crossing of the gorge. Blondin began the crossing at 4:30 p.m. After crossing to Canada, Blondin rested 15 minutes and started back to the American side. On his way back, he stood on his head and did a backward somersault. On Aug. 17, 1859, the Great Blondin became even more daring. He stood on the Canadian side with the 140-pound Harry Colcord. Two looped cords hung from Blondin’s shoulders.

Harry Colcord would ride pickaback on Blondin’s shoulders and back. (Here, in southeast Ohio, people use a variation of pickaback when one person carries another. People in southeast Ohio use the word piggyback.) One-third of the way across, the two had to pause, the first of more rest stops. After arriving on the American side, a huge crowd rushed the two and there was a fear that the crowd would push them over the bank into the river. On Aug. 31, Blondin gave a night performance.

In later crossings, Blondin performed even more dangerous feats. He crossed with baskets on his feet and shackles on his body. He also carried a table and chair and tried to sit down on the rope in a chair. The chair fell into the river. He sat down on the cable and ate a piece of cake and drank champagne. Former President Millard Fillmore came to witness one of Blondin’s 1859 crossings. In 1860, the Prince of Wales (later to become King of England as Edward VII) politely refused an invitation to be carried across the gorge on Blondin’s back.

The Prince of Wales persuaded the Great Blondin to come to London’s Crystal Palace to perform. Jean Francois Gravelot gave performances in Europe until 1896. In 1897, the Great Blondin died in his bed at the age of 71.

Blondin performed at Niagara Falls, New York, for two summers. He had crossed the cable on a bicycle, on stilts, at night and he pushed a stove in a wheelbarrow and cooked himself an omelet while on the cable. His home near London was called Niagara House. Songs were written about him. Imitators followed him, but the Great Blondin was the “Hero of Niagara.”

Niagara Falls, New York has, for a long period of time, been a mecca for honeymooners. Over 10 million people visit Niagara Falls each year, mostly from April 1 to Oct. 31. Several steamers called The Maid of the Mist have taken tourists close to the waters at the base of the falls. Niagara Falls change constantly through erosion. The ledge of Horseshoe Falls (Canadian side) wears away at about 3 inches a year. The ledge of the American Falls (American side) wears away at the rate of one inch per year. Yet, the gorge gets longer and longer as time passes by.

In the 1920s and 1930s, going “over the falls in a barrel” became popular. Several persons have accomplished such feats. However, the barrels have been made of metal, not wood. The metal barrels were strong enough to withstand the great power of the falls. The drop distance when “going over the falls” is slightly more than 160 feet!

— Bob Leith is a retired history professor for Ohio University Southern and The University of Rio Grande.